By Lawrence G. McMillan

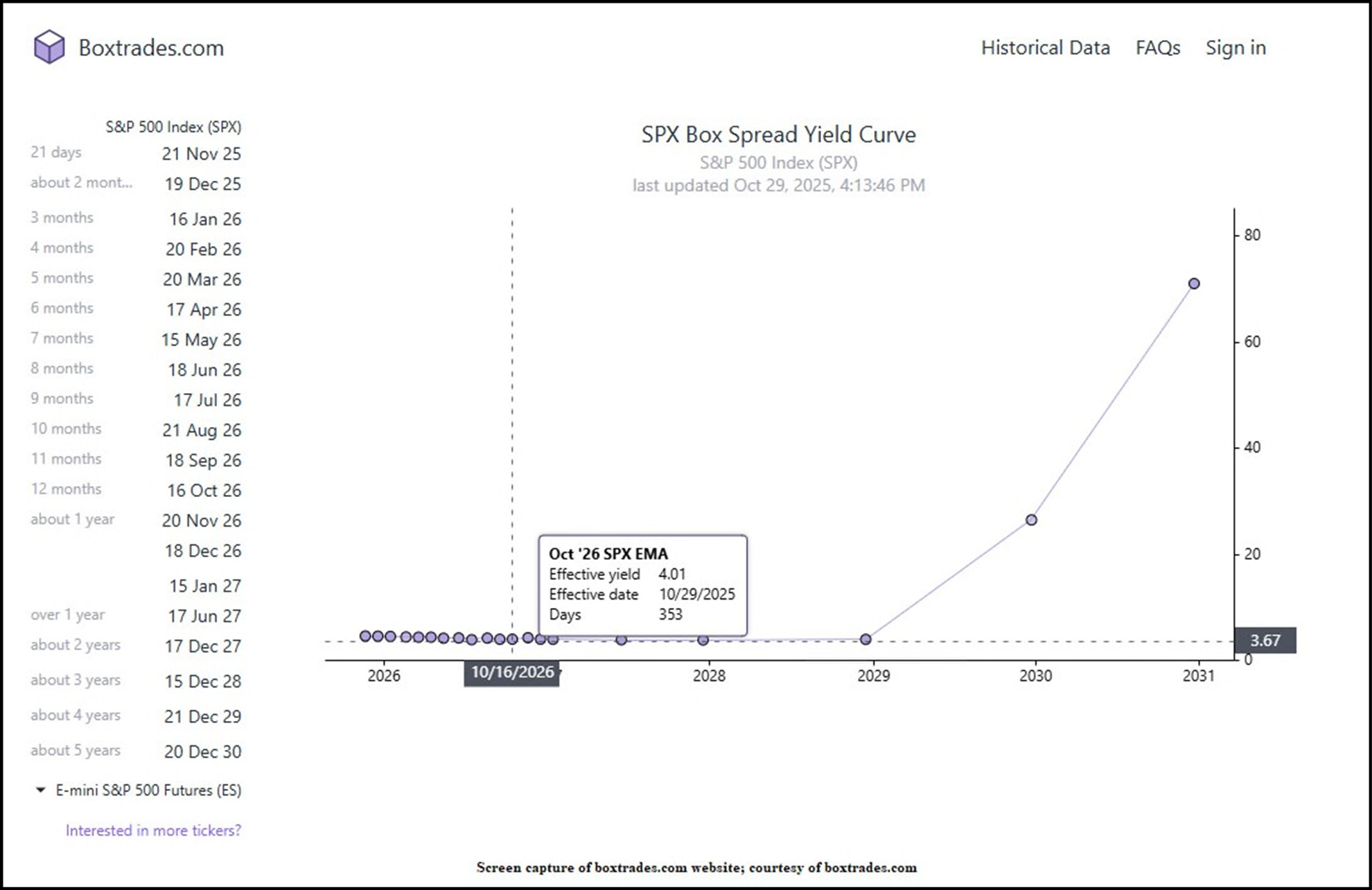

Recently, there have been some articles in the media – both print and social – about box spreads and how people are using them to get reduced-cost loans. Some of these articles lacked full information and others seem to miss the point completely, so we thought we’d explain how this whole thing works.

Definition

A box spread involves four options – two puts and two calls, two striking prices, and all with just one expiration date. It is actually a form of arbitrage that has been available in the option markets since day 1. For example, in a box spread, one might be selling a call credit spread and also selling a put credit spread with the exact same terms. The two effectively cancel each other out in terms of risk, so the profit lies in what prices the spread was established at. Alternatively, one could buy a call debit spread and a put debit spread with the same terms. Let’s look at an example of “buying” a box spread.

Suppose the following prices exist:

XYZ common: 55

XYZ January 50 call: 7

XYZ January 50 put: 1

XYZ January 60 call: 2

XYZ January 60 put: 5.50

A box spread could be established in this example by executing the following transactions: Buy a call bull (debit) spread:

Buy 1 XYZ January 50 call 7 debit

Sell 1 XYZ January 60 call 2 credit

Net cost 5 debit

Buy a put bear (debit) spread:

Buy 1 XYZ January 60 put 5.5 debit

Sell 1 XYZ January 50 put 1 credit

Net cost 4.50 debit

Total cost of position 9.50 debit

No matter where XYZ is at January expiration, this position will be worth 10 points. The buyer has locked in a risk-free profit of 50 cents, since he "bought" the box spread for 9.50 points and will be able to "sell" it for 10 points at expiration. To verify this, evaluate the position at expiration, first with XYZ above 60, then with XYZ between 50 and 60, and finally with XYZ below 50...

Read the full article by subscribing to The Option Strategist Newsletter now. Existing subscribers can access the article here.

© 2023 The Option Strategist | McMillan Analysis Corporation