By Lawrence G. McMillan

This article was originally published in The Option Strategist Newsletter on 7/30/2021.

One of the tougher choices an option trader faces is what to do with a profitable position. That’s a good choice to have, but it might not be any easy one. Our philosophy is always to let profits run. Therefore we use trailing stops, not targets. Targets only take you out of your best positions way before they have run their course. But even within the framework of using trailing stops, there are some choices to be made besides just raising the trailing stop as a long call position gains profits. Specifically, when should a profitable long call be rolled up or a profitable long put be rolled down – if at all?

Example: let’s look at an example. Suppose you bought XYZ Sept 35 calls at a price of 3.00, and now XYZ has made a good run to 41. Assume the 41 strike exists. Here are the current prices:

XYZ: 41 XYZ

Sept 35 call: 7.50

XYZ Sept 41 call: 4.00

To roll up, you would sell your Sept 35 call at 7.50 and buy the Sept 41 call for 4.00, for a credit of 3.50 points, using the prices in this example.

To roll up, you would sell your Sept 35 call at 7.50 and buy the Sept 41 call for 4.00, for a credit of 3.50 points, using the prices in this example. That would make your net investment in this position a credit (you paid 3.00 initially, and now you roll up for a credit of 3.50 points). So, no matter what happens from here on out, you would make at least 0.50 from your various efforts in this XYZ stock – even if the Sept 41 call subsequently expires worthless.

But should that be the main criterion upon which you base your decision to roll up – whether you cover the cost of your initial call? Probably not. In fact, I might argue that is the least important thing to look at. There are really only two choices – roll up or not (let’s not get into the myriad of calls that one might roll into; let’s just say this is the one choice for the roll).

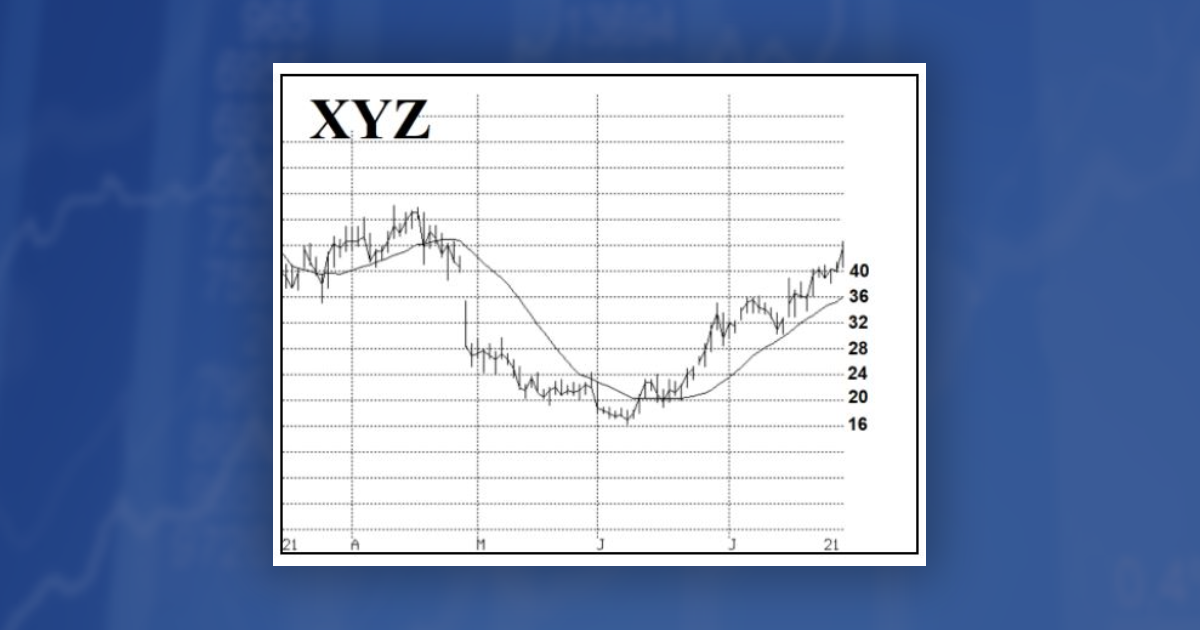

The graph above shows how this stock has been roaring higher, and the trailing stop is on the chart as well – at 36. If we do nothing, and the stock falls below 36, what is our initial Sept 35 call going to be worth? More than 3.50 (which is what we can get for rolling up right now)? That’s a tough prediction to make. If implied volatility is high, that Sept 35 call might still be worth more than 3.50, but we can’t be certain that will be the case (more about this later).

But that’s really what I consider the most important thing to look at: If the stock falls back to the trailing stop, and you have to sell your initial long call there, would you get more for it than you can get for rolling up right now?

Also, note that when you roll up, you are overlaying a bear spread (Sell 35 call, Buy 41 call) on top of your existing long position. This takes a little of the upside potential out of the trade. Suppose, for example, that you did roll up and the stock eventually went to 52 at expiration and you decide to exit. At that point you would sell your long Sept 41 call for parity (11). Your net gain in the trade would 11.50 points (3.00 debit for the original cost, 3.50 credit for the roll up, and then 11.00 credit for the final sale of the Sept 41 call). What if you had not rolled up? Then with the stock at 52, your original Sept 35 call could be sold for 17 (also parity). In that case, you would have made 14 points (bought the call initially at 3 and sold it at 17). So, the roll up cost you 2.50 points (14 profit without rolling up vs. 11.50 with rolling up). The following table summarizes the trades:

Hence, the bear spread took 2.50 points out of the upside profitability of the position. Ideally, you would never roll up if you were interested only in maximizing your profits. But, in reality, rolling up might give you peace of mind – you can’t lose after that, even if the underlying stock tanks. Peace of mind is not a trivial thing to a trader.

Another factor to consider is: how expensive is the Sept 41 call you are going to roll into? If its implied volatility is substantially inflated, then rolling up might not be such a good idea. That is especially true if you think that the inflated volatility would hold for a while. If it does, then even if the stock did fall back to your trailing stop at 36, and the Sept 35 call were to be a participant in the same inflated implied volatility, it might well be selling for more than 3.50, the price of the spread. This implied volatility consideration was a large factor in many of our decisions to roll, or not to roll, very profitable long puts during the “pandemic crash” of March 2020, as implied volatility of index and stock options remained inflated for a long time. When the long option in the roll is trading at an excessively high implied volatility, it argues against rolling and in favor of holding your initial long position – but still being certain to use your trailing stop if it is hit.

In some cases, strikes might be far apart when you look at the roll, or option markets might be wide and illiquid. Those would be arguments against rolling as well.

But, it really boils down to the one question highlighted in yellow above: If the stock falls back to the trailing stop, and you have to sell your call there, would you get more for it than you can get for rolling up right now? This simple question can keep you from rolling too early or too often, and from getting too little credit for rolling up (i.e, from buying a very expensive call), without forcing you into a lot of mathematical analysis.

This article was originally published in The Option Strategist Newsletter on 7/30/2021.

© 2023 The Option Strategist | McMillan Analysis Corporation