By Lawrence G. McMillan

As trading opened on Monday, February 5th, 2018, stocks had already been falling for a few days. Then on that day there was a major decline – the largest drop in point terms in history. The Dow was down 1,175 points. The S&P 500 Index ($SPX) was down 113 points. All other major stock indices suffered similar fates. Those net changes were effective as of the 4 p.m. (Eastern time) close of the NYSE.

Volatility rose, of course. $VIX was up 116% on the day – rising from 17.31 to 37.32. $VIX trades until 4:15 pm Eastern, and the last three points or so of its rise came in the 4:00 to 4:15 time period. The $VIX futures were up substantially by 4 p.m., too, although not quite 100%.

However, as bad as those things were for the U.S. stock market, none was catastrophic for any product as the clock moved to 4 p.m. After 4 p.m., the rebalancing for the various Exchange-Traded Products (ETPs) takes place. In particular, the “short volatility” ETPs – XIV and SVXY – were about to undergo life-changing events. XIV had last traded at 99 and SVXY at 71.82, just before 4 p.m. By the time that $VIX futures had stopped trading at 4:15 pm, both products were in ruins. The Net Asset Value of XIV was about 4!

This demise of the “short volatility” strategy has triggered even more selling in the markets, and its after-effects may extend deeper and last longer than many had expected. The virtual hysteria in the media – even from supposed derivatives experts – has been almost comical. One vociferous commentator made the outrageous statement that, “Nobody understands these products, not even the people who own them.” That certainly is not true, but it may be true that some of the traders left holding the bag on that last day may not have understood exactly what was going to happen – mainly because they had not done their research.

First, Some Background

We had previously written several articles outlining how dangerous a volatility explosion would be for XIV and SVXY. The primary such article was in The Option Strategist in the September 1st, 2017 edition (“Will the Short Volatility Trade Ever Disappear?”). There have been many other, similar articles by many other authors in the last year or so, mostly on web sites that are into things that are a bit more sophisticated.

In order to understand what happened, it is necessary to understand how these volatility ETNs and ETFs are constructed. Barclays introduced the first Volatility ETN – a “long volatility” tracker, with the symbol VXX in January 2009. VXX still exists. Let’s call this a “direct” volatility product because it goes up when volatility rises.

There was one very biased article on Bloomberg recently, where it was asked why do these products even exist – implying there was no economic reason. But there is. When the stock market drops, volatility rises. In fact, in explosive stock market declines, $VIX rises faster than $SPX falls, on a percentage basis. Hence, the main reason that “direct” volatility products exist is to allow one to own volatility as protection for one’s stock portfolio. $VIX is a better hedge against a broad stock market decline than merely owning $SPX puts, say.

However, one cannot trade $VIX itself, for the calculation is too complicated to replicate in an exchange-traded product. The best that one can do is to trade the near-term $VIX futures. But many institutions cannot or do not trade futures (nor do many retail investors), so these ETNs and ETFs were created as a substitute for trading the futures – using $VIX futures as their "underlying." Products in this “direct” category include VXX and VIXY, for example.

VXX is created by owning both of the two front-month $VIX futures contracts, in the same weighted ratio that the $VIX calculation uses.

Example: Suppose that VXX owns March and April $VIX futures. Furthermore suppose that today’s date is February 23rd – a week after the Feb $VIX futures expired. Then the makeup of VXX might be 80% in March futures and 20% in April futures. Each day, the weighting of the front month decreases, and the weighting of the second month increases. So that, at the end of the day on February 24th, Barclays (the market maker and creator of VXX) would have to roll enough futures so that the makeup is 75% March futures and 25% April futures. This takes place daily until the weighting of the March futures reaches 0% at March expiration, and the “underlying” is 100% in April futures. Then the process starts again, with April and May futures.

So each day, Barclays needs to sell the front month futures and buy the second month futures. This is called a “roll,” and there is a cost associated with it. In a bullish stock market, the term structure of $VIX futures slopes upward. That is, the April futures cost more than the March futures, and the May futures cost more than the April futures, and so forth. So, Barclays is buying a more expensive entity (April futures) than they are selling (March futures), on a daily basis. In a bullish stock market, this “cost” takes its toll. VXX will underperform $VIX greatly over time in that case.

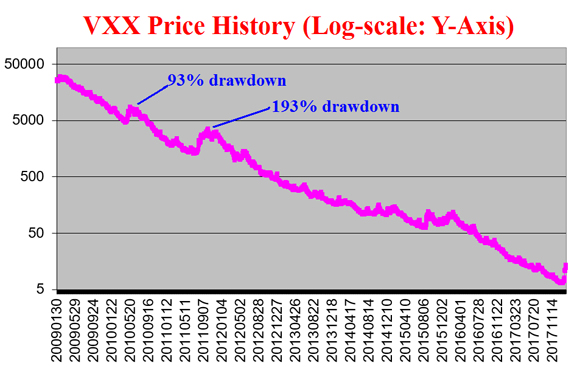

Figure 1

In fact, the price of VXX – from its inception on January 30, 2009, to today – has lost over 99%. There have been several reverse splits over the years, but that doesn’t change anything. For years, we have called this The Big (Volatility) Short. Figure 1 shows a long-term, logarithmic-scale chart of VXX. Adjusted for reverse splits, the value of VXX has dropped from about 26,800 to 7, at its lows in January. You would have trouble finding a better short sale than that. Of course, there were a couple of violent upward reversals (drawdowns for short sellers, as noted on Figure 1), so a short seller would have to avoid those or be wiped out when they occur.

Of course, traders notice profits like these. The “short volatility” trade was initially practiced by mostly professional traders, starting in 2004 when $VIX futures were first listed. They shorted $VIX futures a few months out and covered them when they eventually lost their premium at expiration. That trade blew up in the Financial Crisis, but since it was mostly a professional trade, it didn’t get much publicity amongst all the other carnage that was taking place.

There is one other thing that is important, and will play a part in what actually happened on that fateful Monday: at the end of each day, there is a re-balancing of the exposure of these ETPs. This may be caused by market movement (in $VIX futures) or by new buyers or sellers of the product entering the marketplace. For example, if new buyers of VXX appear, Barclays will sell those VXX shares to the buyer and then must go into the marketplace and buy March and April futures as the underlying for these “new” shares that were created. Similarly, if there are sellers of VXX at some point in time, then Barclays may have to buy those shares back from the seller (if there isn’t another bidder). That reduces the “open interest” in VXX, and then Barclays would have to sell the “underlying” for those shares – i.e., would have to sell both March and April futures. In theory, these actions would not have any material effect on the value of VXX, most of the time. But in extreme market movements, where there is a large change in “open interest,” it could.

Once VXX was created in 2009, other creators of ETPs began constructing directly competing products, as well as the inverse volatility, double volatility, and other types of related ETPs. Almost immediately, the most popular of these was XIV (VIX spelled backwards) – the inverse or “short volatility” ETN. SVXY came later, and it is also a “short volatility” ETF. Let’s concentrate on XIV. XIV was created by Credit Suisse (CS). The “underlying” instruments for XIV are short $VIX futures. As with VXX, the XIV contracts need to be rolled every day, keeping in line with the weighting as in the VXX product and $VIX itself (75%/25%, for example). Only in this case, Credit Suisse has to buy the near-term $VIX futures (reducing its short position in that instrument) and sell the second month (increasing its short position in that instrument). That is also a “roll,” but it is a profitable roll every day in a bullish stock market (when the term structure slopes upward), for CS is selling something that costs more than what they’re buying every day. Hence, this is a big benefit to XIV every day.

Figure 2

The Net Asset Values of these and all other ETPs are calculated each day and posted on various web sites. One of the most convenient places to find this information is merely to go to www.bloomberg.com and quote the ETP. The Net Asset Value is displayed along with the quote.

The creation of XIV allowed even the smallest trader to participate in the “short volatility” trade. It was no longer the purview of hedge funds and professional traders. It was a wonderfully successful trade over the past eight years, for the most part, as the bull market roared upward and volatility was subdued. The profits were especially strong over the past two years (see Figure 2, a graph through 1/25/2018), as XIV rose from about 15 to 148 with very few hiccups along the way – although there were a couple.

As a quick aside, I’ve seen a couple of articles and authors quoted as saying the short volatility trade is like “picking up dimes in front of a steamroller.” That is not true. That phrase applies to selling deeply out-of-the-money options for very low prices, hoping that they will expire worthless. It was popularized in the1980's when “selling teenies” (the cheapest option price at the time was one-sixteenth of a dollar) was thought to be free money – until it wasn’t. In the aftermath of the Crash of ‘87, that strategy was crushed, margin requirements for selling naked options were raised (and remain elevated even today), and the inverse skew that we see in index options today has persisted ever since. I suppose, in some sense, that selling deep out of the money options naked is a “short volatility” trade of sorts, but the current short volatility trade involving XIV had plenty of profit potential as you can see from Figure 2. There was a lot more profit involved than a few dimes.

When there are profits like that, a strategy (short volatility) gets publicity. Hedge funds are created to trade it. CTA’s offer it as a strategy. Articles are written about its profitability, and the net effect is that the trade gets very crowded. By the end, a lot of unsophisticated traders had entered the strategy. The same sort of thing happened with Bitcoin, I’m sure, and with the Cannabis stocks, too (and may still be happening in those venues). I am loosely quoting Warren Buffet when he said that smart money enters a profitable strategy near its creation and unsophisticated money enters near its demise.

The Problem

The profitability of XIV comes from two sources: 1) the daily “roll” generates a profit, and 2) over time, the $VIX futures lose ground vis-a-vis $VIX. In a bullish stock market, $VIX goes nowhere, so the $VIX futures eventually lose ground, and XIV – which is short these futures – makes money. But it should be obvious what the problem is: what if the $VIX futures rise more than 100% in a day? What would happen to XIV? It would be wiped out. The Prospectus explains that clearly. In the afore-mentioned article that I wrote last September, it was described in detail what would happen. Quoting from that article:

“In the case of XIV, if the futures gain 80% on a given day, CS will begin to cover the futures, hoping to cover them all before they rise more than 100%. Holders of XIV can only lose 100% of their money, but if CS has to cover futures more than 100% higher, any further losses would belong to CS. In such a case, CS has the ability to accelerate the expiration of the product, and holders will receive a cash payout for whatever is left (if anything). In that case, the ETN will cease to exist any longer.”

Even if the futures don’t rise 100% in a given day, if they rise anything close to that, the Net Asset Value of XIV will be greatly damaged. As with anything, if it loses 90% of its value one day and regains 90% of its value the next day, it will not be back to where it started, but would rather have lost 81% of its value.

Once again, quoting from the September 1st article:

“The combined actions [of market makers buying $VIX futures in the disaster scenario] would be quite startling and would certainly have after-shocks in other parts of the market. Having traded through the Crash of ‘87, one learns not to discount things like this. In theory, $VIX rose from about 30 to 150 on the day of the Crash of ‘87, so it is certainly possible for a double of $VIX futures to occur in a single day.

Note that this dire scenario would not unfold if, for example, $VIX futures were to rise 50% one day and then 50% again the next day. That would certainly be very harmful to the value of XIV and SVXY, but it would not cause the buying panic in the $VIX futures described above. However, with massive redemptions (selling) of the XIV and SVXY shares by holders of those ETFs and ETNs, there could be massive buying of $VIX futures anyway – perhaps in a more orderly manner – as the underwriters unwound the futures positions to match the redemptions in the shares.”

So those were the known facts. Even so, there were investors, both small and large, that were heavily invested in XIV without much apparent hedge. One fund, ironically, was a “Preservation and Growth Fund.” Many are going to sue. Sue whom? For what? All of these facts were spelled out in the prospectuses of the various ETPs. Most of the warnings were in bold print and repeated throughout the prospectus. As I’ve said before, one has to read the Prospectus to see what could happen, and most owners of XIV had not done so. Even so, if you even had the barest knowledge of what XIV was – that it was short futures – the first thing to come to your mind should be, “What happens if the futures rise by more than 100%?” But in this day of “it can’t be my fault,” you can be sure there will be regulatory – maybe even Congressional – hearings. Let’s just hope they don’t come up with regulations that are overly oppressive and mess with the ability to hedge one’s portfolio by owning volatility.

What Happened?

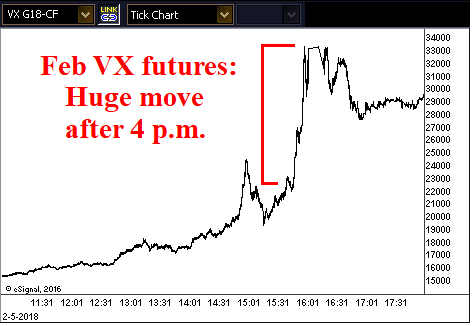

So much for the theory, let’s look at what actually happened after the NYSE 4 p.m. close on Monday, February 5th. As stated above, the market had been crushed and volatility had increased, with $VIX rising from 17 to 37, roughly, during the trading day on that Monday (see Figure 4).

As of that date, VXX, XIV, and the other products were approximately weighted as 35% in February $VIX futures and 65% in March $VIX futures. On Friday, February 2nd, these were the prices:

2/02/2018 prices: Feb $VIX futures: 15.63; Mar $VIX futures: 14.98

It is very important to note that the Feb $VIX futures were trading at a higher price than March $VIX futures – a point we will return to later.

On that following Monday, when the market had gotten slaughtered, the February $VIX futures had risen from 15.63 to about 25 at 4 p.m. They don’t keep 100% pace with $VIX due to several factors – too complicated to go into at this point. The March $VIX futures had risen from 14.98 to about 20. So the percentage increases were bad, but they weren’t in “wipe out’ territory yet.

However, CS needed to do more than just “roll” the futures. There had been heavy selling in XIV that day (it had fallen from 115.5 to 99 by 4 p.m. that day). If you’ll recall, that results in a decrease in the “open interest” of XIV, and CS needed to buy futures to unwind the “underlying” to those shares. So CS entered the marketplace at 4 p.m. with a boatload of orders to buy $VIX futures – both Feb and March. I don’t think there was anything manipulative about this (i.e., CS didn’t have any “hidden” long positions in volatility or short position in XIV). But the buying that needed to be done was massive.

So they drove prices substantially higher. The $VIX futures market is liquid, but their buy orders (and those of the other short volatility product, SVXY, managed by ProShares) swamped the available offerings. They drove the prices of the Feb futures up to 33.23 (remember, it had closed at 15.63 the day before) and March futures up to 28 (it had closed at 14.98). See Figure 5.

So, that was an increase in the Feb futures of +126%! The March futures had increased by 87%. As a result, the Net Asset Value of XIV was theoretically a loss of 96%. That was what was reported, per regulatory ETF guidelines – as if they had bought the futures. I say “if” and “theoretically” because CS and Proshares were unable to cover all the futures they needed. They were able to finish their buying overnight ($VIX futures trade throughout the night) and the next morning, and get slightly better prices. So the NAV of XIV was about 11.60 when all the damage was totaled up.

Figure 3

Figure 4

Figures 3, 4, and 5 show the trading that day in March e-mini futures, $VIX, and Feb $VIX futures, respectively, on Monday, February 5th. Note the “crush” of trading after 4 p.m. It should be noted that massive buying of $VIX futures spills over into other markets, as those with exposure try to hedge themselves. Specifically, it causes selling of $SPX products or buying of puts on those products. CS is obligated to buy the $VIX futures, due to the Prospectus, but when they bought up the $VIX futures, it caused other traders to be short those $VIX futures. If one is suddenly short $VIX futures, you can hedge yourself by selling “the market” (short $VIX futures and short “the market” is a hedge, because they move in opposite directions). Hence, selling spread to other markets (see Figure 3).

There were rumors that CS had taken a huge loss in its market-making operation, but the decline in its stock price has been modest, so that seems to have been a false rumor. Some sources claim that CS had laid off their risk to other players, but in the end, someone had to cover all those short futures.

Figure 5

In the aftermath, CS has decided to accelerate the expiration of XIV, and it will no longer trade after February 20th. At this time ProShares seems to be sticking with SVXY. So for now, it is the most liquid “short volatility” ETP still in existence (VMIN is another). Hopefully, they will continue to remain viable, for the Big (Volatility) Short is an excellent trade that takes advantage of an upward sloping term structure in the $VIX futures. Eventually, when things settle down, the term structure will once again slope upward, and the trade will return to profitability.

Could This Have Been Prevented?

Nothing could have prevented the $VIX futures from rising by 100% in one day. That was always going to happen, eventually. But traders had an early warning system – and thus a way out – by merely observing the slope of the term structure. The profitability of the “short volatility” trade using XIV and SVXY relies on an upward-sloping term structure in the $VIX futures. If that term structure flattens or begins to slope downward, bad things happen to the Big (Volatility) Short trade. The rapidity with which the term structure makes that change has a lot to do with just how bad the losses are that are incurred by the volatility shorts. Most smart players understand that when the term structure flattens or inverts, it is time to get out of XIV. That happened during the day on February 2nd. We saw above, that the Feb $VIX futures settled at a higher price than the March $VIX futures that day. In fact, the term structure inverted fairly early in the trading of February 2nd, and there was ample time to exit before disaster occurred. In reality, smart traders probably exited the trade when the term structure got within 50 cents or so of inverting – and that happened days earlier.

As I wrote in September, “In the articles we previously have written about the Big (Volatility) Short trade, we had exits in mind. Those should be paramount for anyone using this strategy. Simplistically, if the term structure flattens, get out of XIV and SVXY until it steepens again. There is no advantage to being in those securities when the $VIX futures term structure is flat or sloping downwards. The term structure will flatten before disaster occurs.” I have repeated that message in my webinars and seminars since then as well. Hopefully, someone listened.

Some Final Thoughts

It is interesting to note that there is a “free arbitrage” that exists with these products, although it involves some cost to carry. But, in theory, if one is long VXX and long SVXY, in equal dollar terms, then one has a “free daily call” at 100% of the value of VXX. That is, SVXY cannot fall below zero in one day, but VXX could theoretically rise by more than 100% in a day. This time, it wouldn’t have quite worked out. The NAV of VXX rose from 32 to 65 (theoretically) on that Monday, February 2nd, but it never traded at that price. And, when it was realized that XIV wasn’t going to zero, VXX fell back.

There has been a lot of selling of stocks since this event. Is the “short volatility” trade taking the brunt of the blame? Well, it’s certainly taking some blame. I suppose that it isn’t a whole lot different from the Crash of ‘87, which was blamed on Portfolio Insurance, the strategy involving S&P futures. Somehow, it’s always the fault of derivatives, as if no one would ever sell if there weren’t derivatives. In this case, as shown above, massive buying of $VIX futures causes selling in other “stock market” related products. Once selling begins to spread to other markets, the ramifications can quickly grow. This is what happened in the Crash of ‘87, when portfolio insurance dictated that massive amounts of S&P futures needed to be sold, thereby spilling over into massive selling in the stock market. A similar thing happened with the short volatility trade this time, causing “shocked” reactions among stock market analysts and watchers, as they didn’t really understand where this selling was coming from. Of course, as noted earlier, there was already selling going on in the stock market prior to 4 p.m. on Monday, February 5th, but the demise of the short volatility trade added fuel to the fire.

So that’s what happened – even if it took this large of an article to explain it. There was logic behind what went on; it wasn’t just a random event.

Because the term structure will always slope upward in a bull market, the short volatility trade will always be viable during a bull market – even if short volatility ETNs are somehow abandoned or banned. When this all settles down, and a bull market returns, it will once again be time to buy SVXY or related products – if they still exist. Otherwise, one could always short VXX, or buy puts on VXX, or short $VIX futures – remembering to exit if the term structure flattens.

This article was originally published in the 2/16/18 edition of The Option Strategist Newsletter.

© 2023 The Option Strategist | McMillan Analysis Corporation