By Lawrence G. McMillan

This article was originally published in The Option Strategist Newsletter Volume 20, No. 14 on July 29, 2011.

There has been something of a “buzz” in volatility forums and in some media articles about a backspread strategy that is designed to take the loss out of using $VIX options for protection or speculation. As you know, we are running a “perpetual call buy” strategy for long $VIX calls (Position S610). Also, this week we recommended the purchase of $VIX calls as protection for stock portfolios, for those who were worried about what might happen in the event of a downgrade of U.S. debt or a failure to raise the debt ceiling. However, this backspread strategy purports to be better because it allows you to exit before much, if any, loss occurs. As all thinking traders know, however, there is no free lunch. If there’s really no risk, then something else has to give. You’ll see what we mean.

The Basic 2x1 $VIX Backspread Strategy

The strategy that is being espoused is based on a 2x1 call backspread, such as this example using actual prices from a couple of months ago:

$VIX: 17.07 on 5/13/2011 July $VIX future: 20.25 S 1 $VIX July 25 call @ 1.60 B 2 $VIX July 32.5 calls @ 0.80 Outlay: $0 debit

So, what we are attempting to do here, is – on May $VIX derivatives’ expiration date – set up a call backspread: selling one out-of-the-money call and buying two further out-of-the-money calls, where the price of the one being sold is approximately twice that of the one being bought. Note that the options expire two months hence, not one. If one has to pay a small debit for the spread – say, up to 15 or 20 cents – that would work nearly as well.

The main idea behind using this position is that – at least for a while – a 2x1 call backspread acts just like a long call, until the position gets too close to expiration, in which case the losses near the higher strike can become large.

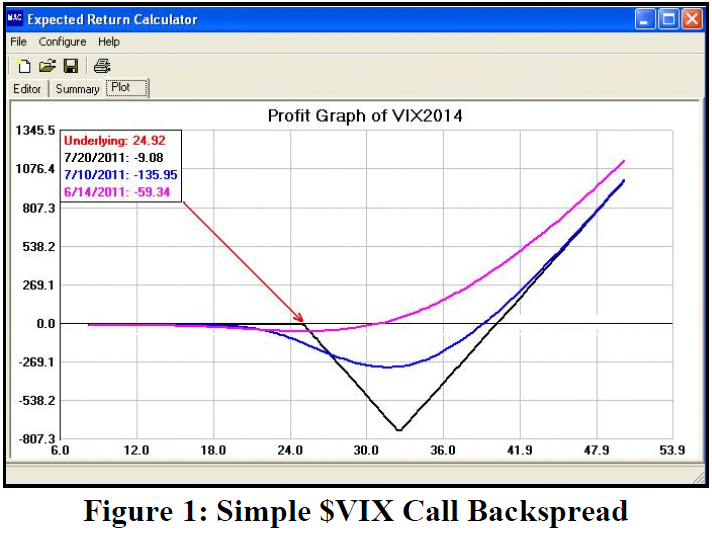

Now, using the McMillan Analysis Corp. Expected Return Calculator, we can evaluate this position. Figure 1 shows the results.

There are three lines in Figure 1. The black line shows what would happen if the position were held all the way to July expiration: There is no gain or loss (except commissions) below 25. Between 25 and 32.5, losses begin to grow, reaching their maximum of 7.5 points ($750) at 32.5 at expiration. Above 32.5, losses diminish until the upside breakeven point is hit at 40. Above there, unlimited gains are possible.

There is nothing particularly attractive about the black line itself. The blue line shows how the position would perform on July 10, 2011 – ten days prior to expiration. Again, relatively large losses of $300 or so are possible near 32. That isn’t very attractive, either.

The true attractiveness of this position is the pink line. It shows how the position would behave on June 14th – the last trading day of the June $VIX derivatives (or about one month before the July derivatives expire). With this much time left until expiration, the pink line barely dips into negative territory at all. The worst point is a small loss of about $60 near 25, with a month to go (see the box inside of Figure 1). Yet, it has plenty of upside profit potential (as do all three lines) because two calls are owned in this spread, and only one has been sold.

If you just look at the pink line alone, it looks very much like the profit graph of owning a long call at some point prior to expiration. The pink line turns sharply upward at a price of about 31 or 32, so July $VIX futures would have to rise to there or above in order for this position to start generating profits with a month to go.

This backspread could thus theoretically be used for strategies where one would normally buy $VIX calls – mainly, as either protection for a stock portfolio, or as outright speculation on a large increase in volatility.

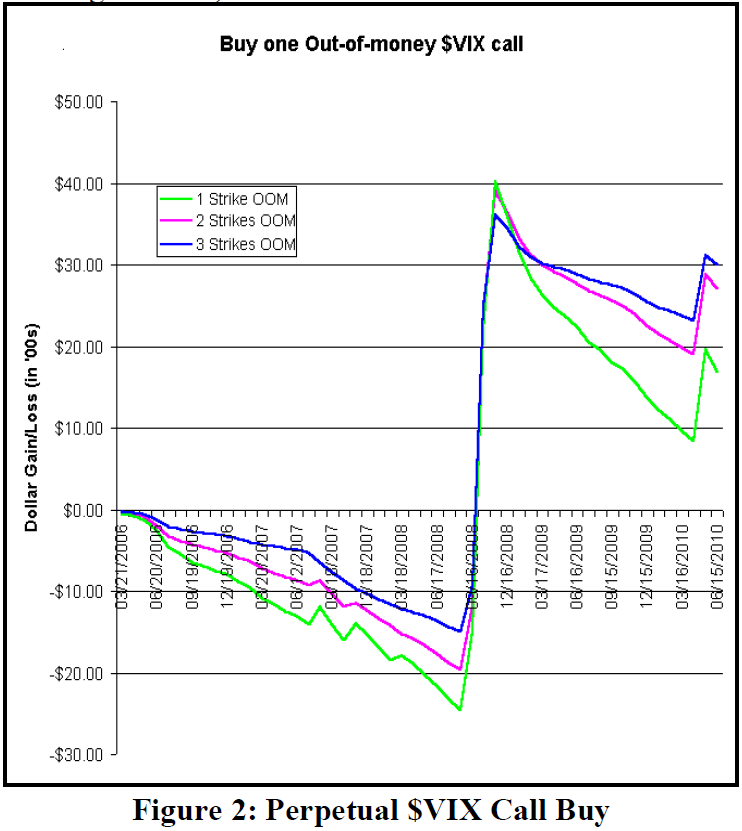

As longer-term subscribers know, we have done research on the subject of buying $VIX calls as protection or speculation, and we proved that, to date, one could have made money – good money – by merely buying the one-month $VIX call, three strikes (7.5 points) out of the money, and rolling it over at expiration. The profits from the two explosive moves in $VIX – October, 2008, and May 2010 (the “flash crash”) – were more than enough to offset the long list of small monthly losses.

In Volume 19, Issue 13 of this newsletter, we explained the “perpetual call buy” of $VIX calls and began Position S610, which does exactly that – buys the near-term $VIX call three strikes out of the money and rolls it over each month.

Figure 2 shows the profit graph of the “Perpetual Call Buy” since inception of $VIX option trading in February, 2006. The dark blue line is the one that shows the profits and losses of buying the call that is three strikes out of the money. It performs best for the simple reason that, in losing months, you spend less on the deepest out-of-themoney of the three calls shown, but in times of crisis, $VIX explodes so far to the upside that all three strikes go deeply into-the-money.

Figure 2 only shows the results through June, 2010. At that time, the blue line showed a profit of 30 points ($3,000) per contract. Since then, $VIX has not made a major move upward, and the purchase of one near-term contract has lost about $750, so the net result to date for this strategy would be a gain of $2,250 per contract. That’s still a huge return, considering that the average monthly cost for one contract is about 60 cents ($60), and the maximum drawdown was about $1300 (Feb 2006 to August 2010).

We don’t have a comparable track record for the backspread strategy because its construction is a bit more complicated than “buy one call three strikes out of the money.” If time permits, I may try to put together such a track record for the backspread strategy, but I am not terribly motivated to do so, because of what I am about to discuss.

Drawbacks

So, is this 2x1 backspread really better than buying a short-term call? I would argue that it might not be.

The entire strategy behind the 2x1 backspread is more complicated than just described. There are articles about it on the internet, although most are written by financial reporters and not strategists. One, written after the Futures & Options World European Equity Options Conference in Amsterdam this past April is available from the FOW web site1 (click to read).

But the crux of the strategy is simple: one establishes the 2x1 backspread and then rolls to the next expiration before losses start to set in. Simplistically, this means that the position is established two months before expiration and then rolled one month before expiration.

The strategy was also presented at the CBOE Risk Management conference this past spring, in a presentation by Societe Generale (SocGen) and Peak 6 – both noteworthy “think tanks” in the volatility space. They, too, concluded that an out-of-the-money 2x1 call ratio spread using the second month and rolling one month prior to expiration was better than a systematic long only volatility position. At that conference, one discussion of the strategy was presented by Societe Generale. A pdf of that presentation can be found here.1

On the surface, the backspread strategy seems very attractive. Perhaps if one is merely looking to speculate on volatility, it might be appropriate, but I think there are two major flaws in this strategy. One flaw has to do with the term structure of $VIX futures. As we know, the options trade off the futures and not $VIX. Furthermore, in a severe bear market, when $VIX explodes to the upside, the term structure turns negative (i.e., all the futures trade at a discount to $VIX). When that happens, the backspread strategy – since it is the second month and not the front month – may not produce the desired gains.

In the SocGen paper, the comparison is made between the 2x1 backspread and buying a .20-delta $VIX call in the same month as the backspread. That last phrase is the key; they didn’t compare the backspread to buying a .20-delta call in the front month.

The simplest way to illustrate this is to look at the worst bear market since $VIX derivatives have been listed – that of October, 2010. At one point, the following prices existed, roughly:

$VIX: 70 on 10/10/2010 Oct $VIX future: 56 Nov $VIX future: 38

A long Oct $VIX call is 18 points farther in the money than a November 2x1 call backspread!

As October expiration approached, $VIX stayed near 70, and so the Oct futures sucked right up to 70. Meanwhile, November futures rose only into the mid-40's.

I suppose a counter-argument would be to buy more of the November 2x1 backspreads as opposed to outright long October calls. That’s fine, but there is also a big difference in the margin required.

The margin for a backspread is the difference in the strikes, plus any debit incurred in establishing the spread. Obviously, the only requirement for an outright long call is merely to pay for the call. Even if the 2x1 backspread is using strikes 5 points apart (not always possible, if one wants to pay only a small debit for the spread), this is how the comparison would look vs. an outright long call at 0.60:

Margin Comparison 2x1 Call Outright Backspread Long Call for $0 debit: For 0.60: $500 $60

So, it might be easy to say “do more backspreads,” but it’s more costly to do so, in terms of margin requirements. This could be significant, say, if one were trading long stocks fully margined, or selling naked index or equity puts with the full equity in the account. In that case, one would likely have to close down some of the account’s “main” strategy in order to fund the backspreads.

The term structure wasn’t so critical during the other big move in $VIX – May of 2010. The term structure remained amazingly flat during that time period, so there was very little difference between the June and July futures. Even May futures traded at a deep discount to $VIX itself, with less than a week to go until expiration.

The Most Important Flaw?

Term structure is important. But I think the major flaw is where the profit potential arises. We saw from Figure 1 that, using the backspread, the profit potential kicks in at just below the level of the higher strike in the backspread (31 or 32 in the example). That is likely to be much farther out of the money than the “three strikes” we are recommending for our long call purchases.

Using the data from the example for Figure 1, an outright long call would have used the June futures, and they were trading at 18.65 at the time. Three strikes out of the money would be the 25 strike (one: 20; two: 22.5; three: 25). Thus, you’d be long a June 25 call. The outright June call would start making profits well before the backspread did.

I said earlier that if there is really no risk, then something else has to give. As you might expect, that “something” is the profit potential. You just can’t get away from the fact that less risk means less profit potential, no matter how creative your derivatives strategy might be.

Follow-Up Strategies

Something that is addressed in some of the blogs is that the 2x1 strategy would be difficult to continually roll – especially after $VIX has moved up sharply. This is certainly a valid concern, although I’m sure a decent amount of thought has gone into that situation, by the designers of the strategy.

In the simple long call, one would merely use the same strategy as with any long call – a trailing stop and perhaps also rolling the long calls up to a higher strike, in order to extract some credit out of the position. We used that strategy successfully in October of 2010, and there’s no reason to feel it would be any different at any other time.

In essence, the same thing could be done with the 2x1 backspread for, if the underlying rises far enough, the backspread eventually behaves just like one long call. There might a bit of a problem if the long calls were rolled up to a higher strike, for that would raise the margin requirement in the backspread (the difference in the strikes is the major portion of the margin requirement).

Summary

The 2x1 backspread strategy is certainly interesting, and has a certain appeal because losses are minimal if the position is rolled well before expiration. The FOW reporter predicted that “You‘re going to start hearing a lot more about the 1x2 [sic] in 2011.” I guess this article proves he’s right about that. However, in the most dire crisis, the strategy will not perform nearly as well as a front-month call purchase does. In my mind, that makes all the difference in the world. I would rather pay the small amount for the outright long call in order to have my protection “kick in” at a lower volatility level and to more closely adhere to movements in $VIX on the upside.

This article was originally published in The Option Strategist Newsletter Volume 20, No. 14 on July 29, 2011.

© 2023 The Option Strategist | McMillan Analysis Corporation