By Lawrence G. McMillan

This article was originally published in The Option Strategist Newsletter Volume 10, No. 5 on March 8, 2001.

We receive a lot of questions here at McMillan Analysis Corporation – most of them come in from the Q&A section on our web site. The more generic (and interesting) questions and answers get posted on the site. Those that are specific get a personal email answer. One way or the other, they all receive an answer – although we do not comment on specific stocks or specific positions in your trading account. We also hear a number of questions at seminars (so far this year, we’ve attended four seminars), and that is where we got the idea for this article. One topic that people seem to want to discuss is that of “covered writing against LEAPS.” Many people think this strategy has little or no risk, based on some sort of historical studies.

I don’t know about the studies, but I do know that every strategy has risk – even “risk-free arbitrage” – whether it’s a market risk, a credit risk, or a back office (delivery) risk. Most certainly, writing calls against LEAPS has risk. Let’s examine the strategy as most people attempt to apply it, in order to detail the risks and rewards.

One common approach is to buy a LEAPS call option that is slightly in-the-money – with perhaps two years or so until expiration. Then, the owner of that LEAPS call plans to write short-term at-the-money calls against the LEAPS call. Usually, one arrives at this approach by noticing that repeatedly writing short-term calls should completely cover the cost of the LEAPS call after a year or so.

Example: Make the following assumptions: XYZ is trading at 105. It is January, so an April call has 3 months of life. There are two-year LEAPS calls available.

XYZ: 105 April 110 call: 6 (3-month call) Jan 100 call: 26 (2-year LEAPS call)

If you were to use an options model to determine the implied volatilities of these two options, you’d see that the LEAPS call trades with a slightly lower implied volatility (32%) than the near-term call (34%). That is fairly typical of these situations. So let’s examine the purchase of the LEAPS call and the sale of the April call.

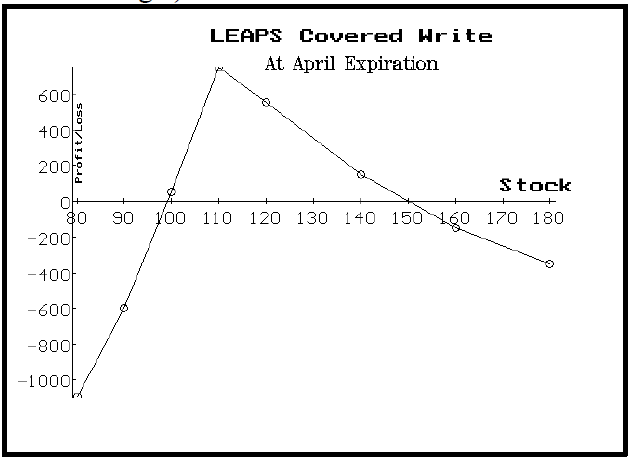

You can see that, if one were able to repeat this same sale of three-month options four times, he would have virtually covered the cost of the LEAPS options. That would take a year, and most certainly the position would be showing a large profit – not to mention the fact that he would still have another year in which to write more calls or to allow the stock to rise if he were bullish. Of course, there would be some risk if the stock fell, but most people discount that because they know they can write repeatedly against the LEAPS calls. The profit picture at April expiration – at prices surrounding the strike looks like the graph below:

That’s the optimum scenario, though. In fact, if XYZ makes a big move during the three-month life of the April call, there is considerable risk – and that risk manifests itself both on the upside and the downside. Notice that the original position involved a debit of 20 points – the 26 paid for the LEAPS call less the 6 received from the sale of the April call.

On the downside, if the stock were to drop dramatically, then that 20 points would be at risk. Obviously, one could write near-term calls at lower strikes against the LEAPS call, but that presents its own set of problems – which we’ll get to later.

Upside Problems

On the upside, there are also problems. Note that the striking prices in this spread are 10 points apart, but the spread cost 20 points. If the stock were to rise so far that the LEAPS call lost most of its time value premium, then the position would start to lose money on the upside. The graph below once again depicts the profit picture at April expiration, but now the X-axis is expanded to show a much wider range of prices. You can see that losses occur on both ends, if the stock moves far enough. Admittedly, it is not probable that the stock could move that far in three months’ time, but it is possible. One note about the upside risk: the LEAPS call will always retain some time premium, so the maximum upside risk is something slightly less than the difference in the strikes less the original debit. In this example, the difference in the strikes (10) less the debit (20) would imply that one could lose 10 points on the upside if the stock rose so far as to cause both options to lose all of their time value premium. However, you can see from the graph below that the maximum risk appears to be closer to 5 points than 10 points. This is because of the time value that will remain in the LEAPS calls (a function of interest rates, no matter how far in-the-money the LEAPS calls get).

The upside risk is often overlooked by many people employing this strategy, because they generally think that bulls spreads and covered writes have no upside risk. However, this spread does have risk because the striking prices are too close together. In order to eliminate the upside risk, one must ensure that the striking prices are nearly as wide apart as the debit of the spread.

One way to ensure that the spread can make money no matter how far the stock rises, is to lower the strike of the LEAPS call that is bought. For example, other 2-year LEAPS calls that might have existed at the same time as the calls in the above example would be:

Jan 60 LEAPS call: 52 Jan 70 LEAPS call: 44 Jan 80 LEAPS call: 37

If one bought the Jan 60 LEAPS for 52 and sold the April 110 call for 6, as before, that would be a debit of 46 points – and the difference between the strikes is 50 points. Thus, this version of the LEAPS covered write would have no upside risk.

Rolling Down

Now, let’s turn our attention to the downside once again. If we use a large-debit spread, there is considerable risk on the downside. Many practitioners of this strategy feel that the downside really isn’t a problem, though, because they’ll just sell at-the-money calls when the April calls expire.

However, remember that when the striking prices are closer together than the debit of the spread, then there could be losses on the upside. To put it another way, if one rolls down the written option to lower strikes, he will eventually lock in a loss if the stock should suddenly start to rise again. The following example describes one such scenario:

Example: XYZ is 105, and a LEAPS covered write is established with options whose striking prices are 50 points apart:

XYZ: 105 April 110 call: 6 (3-month call) Jan 60 LEAPS call: 52 (2-year LEAPS call)

Initially, the Jan 60 LEAPS call is bought (for 52) and the April 110 call sold (for 6) – a total debit of 46 points. Within three months, though, assume the stock has experienced a severe problem and is now trading at 80. Even allowing for a probable increase in implied volatility, a 3-month at-themoney call will probably not sell for more than 8 with the stock at 80.

So, assuming that the April 110 call expired worthless and the July 80 (3-month) call was sold for eight at that time, the result position would be:

XYZ: 80 Long Jan 60 LEAPS call Short July 80 (3-month) call Net total debit in position: 52 – 6 – 8 = 38.

That is, the debit expended to date would be the original 52 points spent for the Jan 60 LEAPS call, less the two premiums received from selling 3-month options (6 and 8 points, respectively). Now, the debit (38) is greater than the difference in the strikes (20) and hence the upside problem arises once again. If XYZ were to rally strongly over the next three months, losses could occur on the upside. In addition, there is still downside risk to the tune of 38 points (the debit).

You might say “well, I just won’t roll down so far as to lock in a possible upside loss – I’ll just write an option whose strike price is high enough in order prevent that.” That sounds great, but in actual practice the 3-month call with such a high a striking price would probably not sell for much. In the above example, for instance, when it came time to sell the July call to replace the expired April call (the stock is 80 at that time, remember), then a July 105 call would sell for about 2 points or less. If you wrote that call, your debit in the spread would then be 44 points (the original 46 points less the two points you get for selling the April 105 call) and the difference in the strikes would be 45 (105 minus 60). That’s wide enough to eliminate upside loss, but your downside risk is now the net debit of 44 points and further stock declines will repeat the scenario.

One strategist recently told me that he was buying $SPX LEAPS at least 100 points in the money and then writing near-term, at-the-money calls against them. He had obviously figured out the upside problem, but his downside could still be problematic.

Rolling Up

We have already seen that there could be problems if the stock moves up too far, too fast. But there is a more general upside dilemma that faces practitioners of this strategy when the stock moves up: should you roll up for a debit? Or just close out your position and start over?

Example: Assume that the original position was the same as the previous example:

XYZ: 105 Buy Jan 60 LEAPS call for 52 Sell April 110 (3-month) call for 6

Later, assume the stock advances modestly, so that at April expiration, the stock has risen to 125. At that time, the following prices exist:

Jan 60 LEAPS call: 70 April 110 call: 15

At this point, the LEAPS covered writer has an unrealized profit of 9 points (he paid a 46 debit to establish the trade and he could take it off now for a 55 credit: 70 minus 15).

However, his original intent was to continue to write near-term calls against this LEAPS call. But the at-the-money July 125 call is going to be selling for something like nine points. Hence, if one wants to continue to write an at-the-money call, he is going to incur a debit to buy back the previously written April 110 call (for 15 points) and sell the July 125 call, say (for 9 points).

The fact that a debit is required to keep the position in place is often contrary to what the LEAPS covered writer was expecting in the first place, for he had planned to bring in a series of credits to eventually reduce the net cost of his long call to nearly zero. Adding debits seems contrary to that purpose.

There is nothing wrong with rolling up for a debit, but most “covered writers” are reluctant to do so because they think of the strategy as one in which brings in credits to his account or closes out the position. However, if one were to roll the April 110 calls up to the July 125 calls for a 6- point debit, he would have the following net position:

Long Jan 60 LEAPS call Short July 125 (3-month) call Net debit to date: 52

This net position is still attractive. First the debit (52) is less than the distance between the strikes (65), so there is no upside problem. Of course, there is still a downside problem – even a slightly larger one than before – because of the large debit in the position.

Probabilities

One thing that we haven’t discussed so far is the probability of these various events occurring. For example, look at the second profit graph on page 2. You will notice that the original LEAPS covered write (in which the April 110 call was sold) makes money if the underlying is between about 98 and 150 at expiration (XYZ started out at 105 in this example). According to our Probability Calculator 2000, there is roughly a 60% chance that the stock will be within that profit range at expiration – with most of the “problems” occurring on the downside, since the downside breakeven point of 98 is quite close to the initial stock price of 105.

Thus, in reality, the LEAPS covered writer in this example will probably not be dealing with the “upside loss” problem. However, he is more likely to have to deal with rolling down – and, of course, he may have to be concerned with rolling up for a debit at expiration, as discussed in the previous section.

Summary

LEAPS covered writing seems to be a fairly popular strategy at the current time, judging by the number of people that I find asking about it. However, it is not as “foolproof” as many traders seem to view it.

There can be problems if the stock drops too far, for one may be forced to lock in a loss. In addition, if the striking prices used in the spread are too close together, then there can be upside losses as well.

Despite the problems associated with large stock movements, the probabilities are “high” that good things will happen. That’s true of any writing strategy. It’s what happens at those improbable times that can harm a writing strategy – whether it’s a naked write, a covered write, or a LEAPS covered write. When dealing with stocks, those “improbable” events are generally more likely than one would normally envision.

Overall, this strategy seems “okay” but not great. It seems that, eventually, one will find himself fighting against upward stock price movements – either because his strike prices were too close together initially, or because he was forced to roll down at some time and, by doing so, his striking prices once again got too close together. A subsequent rally then produces the problem. So, if you’re going to practice this strategy, be ever mindful of the potential upside problems – they are greater than most inexperienced traders envision.

Finally, be sure that you have option modeling software, so that you can draw or map out the profit pictures as shown on page 2 – before you enter the trade. This will also allow you to monitor the upside risk, for when the overall delta of the position becomes negative (as it will when the stock rises enough to cause problems), then you might want to take some defensive action at that time rather than waiting for expiration.

This article was originally published in The Option Strategist Newsletter Volume 10, No. 5 on March 8, 2001.

© 2023 The Option Strategist | McMillan Analysis Corporation