By Lawrence G. McMillan

This article was originally published in The Option Strategist Newsletter Volume 9, No. 13 on July 13, 2000.

Most option traders – even fairly novice ones – understand that options can be used to protect a stock holding against loss. However, when one delves into the specifics of establishing such protection, he usually forsakes the protection, often due to apparently high costs. In this article, we’re going to re-visit a subject that we’ve discussed before (protection), but try to bring some facts to light that might not be understood by many stock owners. The reason that we think this might be an apropos topic now is that it’s July, and July has marked a peak for the market in each of the last two years. There is some evidence (page 5) that a similar scenario might be unfolding again this year.

When one is considering using options as an “insurance policy” against large downside losses in his stock portfolio, he quickly comes to the conclusion that put purchases are the preferred strategy. A put purchase affords one complete downside protection below the striking price of the put, while still allowing for upside profit potential if the market should rally. These features make put buying more attractive, say, than selling covered calls – where the amount of downside protection is normally small, percentage-wise, or selling futures against the stock portfolio – a strategy which eliminates both profits and losses.

Having made that decision, one must also decide whether he wants to buy puts on each individual stock in his portfolio, or if he wants to buy an index put. The index put has the advantage of ease of purchase (one option order takes care of everything, as opposed to putting in numerous orders – one for each stock in your portfolio). However, index puts tend to trade (far) above fair value and there is always the risk that one’s portfolio will not really perform like the index does. Hence, in today’s market, many “insurers” are using equity options.

Even so, the cost of buying equity puts can be quite detrimental to one’s overall portfolio return. This fact causes insurers to search for a strategy that affords protection, but doesn’t cost so much.

The "Collar"

Eventually, via the logical thought progression outlined above, the insurer usually arrives at the “collar” strategy. It is one that we have described many times before, and it is a fairly simple one: buy puts to protect your stock holdings, and at the same time, sell out-of-themoney calls to cover most or all of the cost of the puts. This strategy leaves one with profit potential similar to a call bull spread – limited risk and limited profit potential.

There are some nuances that can be incorporated by altering the striking prices of the puts and the calls in this strategy, some of which allow room for upside profit potential on at least a portion of one’s stock holdings.

Example: Assume that one owns 1000 shares of XYZ. Suppose XYZ is trading at 100, and that the following option prices exist for December options:

Dec 120 call: 7 Dec 110 call: 10 Dec 100 call: 14 Dec 90 put: 7

A simple collar can be constructed by buying the Dec 90 puts at 7 and selling the Dec 120 calls at 7. Thus, the “insurance” costs nothing – except the forsaking of profits above the call strike price of 120. Losses are limited to the strike price of the puts (90), which is 10 points below the current stock price.

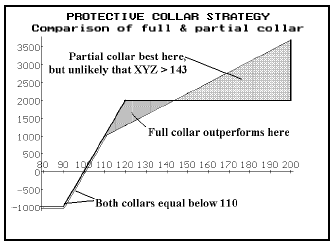

A more “complex” collar can be constructed by using the other calls. For example, suppose that one buys 10 of the Dec 90 puts at 7 – thereby completely hedging his 1000 shares of stock – but now he sells seven of the Dec 110 calls for 10 points each. Again, his outlay is zero, he has protection below 90, but now there is the possibility for partial participation in large upside moves by XYZ (should they occur) since only seven calls have been sold against the 1000 shares of long stock. The profit graph at the top of the next column compares the two collars.

In the above graph, the darker lines represent the profitability of the “normal” collar – limited risk and limited profit potential. The other lines represent the partial collar. As you can see, the partial collar outperforms if XYZ is above 143 by expiration – an unlikely event, but some stock owners feel better having the upside potential and so will use the partial strategy.

Finally, note that in the above example, one could also construct a collar by buying 10 of the Dec 90 puts (full protection for the stock holding) and selling five of the Dec 100 calls for 14 each. This partial collar would have more upside profit potential that the one shown above, but XYZ would still have to rise to 140 before this collar outperformed the “normal” collar.

LEAPS

Longer-term subscribers may recall the collar hedge that took place in the over-the-counter-options market last fall. A company owned 3 million shares of CSCO and wanted to hedge it. With CSCO at 120, it turns out that a 3-year put struck at 120 and a 3-year call struck at 200 (assuming volatility is 50%) sell for the same price! Therefore a “normal” collar was established, giving the stock owners protection below 120 and room for profit potential all the way up to 200 – all for no cash cost. An excellent trade.

While smaller investors cannot avail themselves of the OTC option market, they can use LEAPS options to accomplish similar purposes if the strike prices exist.

To that end, we used the Black-Scholes model to lay out some theoretical solutions to the question, “How far out-of-the-money can I sell a call that covers the cost of an at-the-money put (strike price 100) that I purchase?”

Highest Call Strike That Pays for At-Money Put Vty 2003 LEAPS 2002 LEAPS 30% 130 120 40% 135 120 50% 140 120 70% 150 125 100% 170 130

To understand how to read the above table, look at the bottom of the left hand column. This shows that, using a volatility of 100% (quite high, but not out of the question for some internet stocks), one could buy the 2003 LEAPS at-the-money put and sell a 2003 LEAPS calls struck at 170 for the same prices. So, to determine what kind of a no-cost collar you could theoretically construct for your favorite stock, follow these steps: 1) look up the volatility on our web site (www.optionstrategist.com), 2) look up that row in the table. If your are willing to forsake stock profits above the call’s strike in return for no downside risk, then place an order to the floor to both buy the put and sell the call and see if the floor traders have any interest.

The right-hand column in the above table shows how drastically the call strikes drop when the 2002 LEAPS are used instead of the 2003 LEAPS. In fact, if one uses even shorter-term options, the picture looks even more bleak. Thus, if one is going to use non-LEAPS options for protection, he should probably consider buying out-of-themoney puts (as in the first example on page 2). In that case, he can use slightly out-of-the-money calls to pay for the puts, and still have decent room for profit potential between the strike prices of the puts and the calls.

In fact, there are certain to be many combinations of calls and puts where the sale of the calls pays for the protective put. It is up to the individual investor to decide for himself a) how far out-of-the-money (if at all) he wants his put protection to be, b) how much upside profit potential he is willing to forsake in order to obtain the protection, and c) if he is willing to pay for the protection or if he insists on a “no-cost” collar.

In closing, here’s perhaps the simplest strategy of all: use only at-the-money options to begin with. An at-themoney call will sell for more than an at-the-money put – especially if there is a reasonably long period of time until expiration. For example, these prices might exist:

XYZ: 100 Jan (2003) 100 LEAPS call: 36 Jan (2003) 100 LEAPS put: 24

A very simple protection can be obtained by buying enough puts to hedge all of one’s stock and then selling two-thirds as many calls to cover the cost of the puts (this works, since the price of the put is two-thirds the price of the call). This strategy probably won’t appeal to many because it doesn’t allow for any appreciation by the two-thirds of the stock position that has covered calls written against it. However, it is nothing more than the “collar” strategy carried to the extreme – using only one strike price. Viewed another way, though, one is selling “Jan 2000 futures” against two-thirds of his long stock position, and using the proceeds to buy the rest of the puts. If and when the SEC and CFTC ever agree that “stock futures” contracts can be traded, this will probably be a viable strategy for those looking for protection.

This article was originally published in The Option Strategist Newsletter Volume 9, No. 13 on July 13, 2000.

© 2023 The Option Strategist | McMillan Analysis Corporation