By Lawrence G. McMillan

This article was originally published in The Option Strategist Newsletter Volume 6, No. 3 on February 6, 1997.

At the Futures South Conference last month, there was a lot of talk about delta neutral strategies. We're going to take a look at what these strategies are, and why they're not as profitable and easy to operate as some advisors would have you believe. I have mentioned in the past that I have some trepidation that too many traders are embarking on delta neutral strategies without understanding that — like any other strategy — they involve work to operate profitably.

The attraction of a delta neutral strategy is that, in theory, one does not have to predict the price movement of the underlying security. Rather, he sets up a delta neutral strategy (which should have some other "edge" — in terms of volatility, perhaps) and can theoretically make money because of his "edge", regardless of what happens to prices. That's the theory. In practice, it's a lot harder than that. Let's look at some actual delta neutral strategies.

All delta neutral strategies require at least two different options to be in the position, for the way we determine delta neutral is to divide the deltas of the two options in question.

For example, suppose IBM is at 157, and we want to establish a delta neutral call ratio spread using the Feb 155 and Feb 165 calls. The delta of the Feb 155 call is 0.60 and of the Feb 165 call is 0.25. To determine the delta neutral ratio, merely divide the two deltas: 0.60/0.25 = 2.4, or 12 to 5. So buying 5 and selling 12 would be a delta neutral spread.

The above example is that of a neutral position involving naked options. However, one can also establish a delta neutral position with only long options.

Example: again using IBM, suppose that you think the stock will be volatile, so you want to own some options. The April 160 call has a delta of 0.50 and the April 150 put has a delta of –0.30. The neutral ratio between these is 0.50/0.30 = 1.67, or 5-to-3. Thus if we were to buy 5 of the puts and buy 3 of the calls, we would have a neutral position.

Delta Neutral Is A Fleeting Concept

Most of the hedged positions that we recommend in The Option Strategist, for purposes of volatility trading or for trading the volatility skew, are roughly delta neutral to begin with. And therein lies the rub: any delta neutral position is only delta neutral to begin with. Delta changes as soon as the underlying price changes, or when time changes, or when volatility changes. Thus, it is a virtual certainty that the deltas will soon change, and it is therefore quite likely that your delta neutral position won't be neutral any more. Once your formerly delta neutral position takes on a delta long (bullish) appearance or a delta short (bearish) appearance, you are then once again in the business of predicting prices, which you supposedly didn't want to do in the first place. You have two choices at that point: first you can re-neutralize your position by buying or selling a few options, but the commission and adjustment costs can become quite large if you do this repeatedly (in fact, the only traders who keep their positions extremely neutral are exchange members and market makers who are trading without commission costs). Second, you can handle the position by trying to predict prices.

Even if you do adjust to delta neutral, you are in effect predicting prices to a certain extent, because your adjustment affects the total outcome of the position.

Example: assume that you had established the IBM call ratio spread on the bottom of page 1, having bought 5 Feb 155 calls and sold 12 Feb 165 calls. Shortly thereafter, IBM makes a quick move to the upside and is trading at 172. You are now nervous because your position is quite delta short and you stand to lose a great deal of money if IBM were to continue rising rapidly. Therefore you decide to buy something (it doesn't matter what for the purposes of this example — either stock or some calls) to reduce your risk and reestablish a neutral position. While it's true that your adjusted position may be delta neutral once again, you have in effect said that you don't think IBM will fall in price (if you did think that, you wouldn't bother adjusting). So, in effect, even neutralizing the position involves a market prediction.

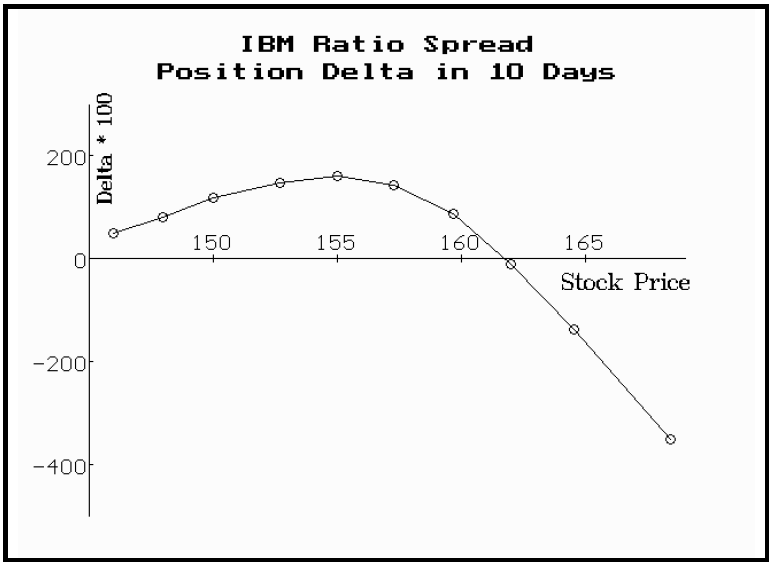

In general, the following graph shows how the delta would change in ten days, at various IBM stock prices. Note that even if IBM stays right where it is, the position starts to become delta long (the curve in the graph is above the axis), while if IBM begins to rally, the position can become quite delta short.

The same sort of thing happens — even more dramatically — in the case of the long straddle. Alex Jacobsen, who heads up The Option Institute (the CBOE's instructional arm), has a good way of describing this: he says that owning a straddle is not a neutral position at all; it's merely a position waiting to tell you in which direction you're going to be trading the market. That is, if the underlying rises in price, you are quickly delta long if you own a straddle, and therefore you trade it as if it's a long position. On the other hand, if the underlying declines in price shortly after you've purchased a straddle, you become delta short and are forced to trade the position as if you were short.

There is nothing wrong with this. In fact, it's often a good way to get into a position before a breakout. We recommend a lot of long straddles in this newsletter, and as you see if you pay attention to our follow-up action, we usually try to ride with the trend — once one is established by a breakout. That's why we're still long the Swiss Franc puts in Position F122: once the currency broke out to the downside, we sold off the long calls and have held the puts with a trailing stop, building up very good profits as the trend continued.

These examples should have amply demonstrated that a "delta neutral" position quickly becomes price sensitive — thereby negating the supposed "advantage" of the concept of not having to predict prices. So, you might ask, "Why bother with this delta neutral business when I just wind up having to predict prices anyway?" Good question. The answer lies in the fact that there are often times when you can have an advantageous position that doesn't require much attention for a while. Then, when it does, you may already have a profit or may be able to remove the position with only a small degree of risk.

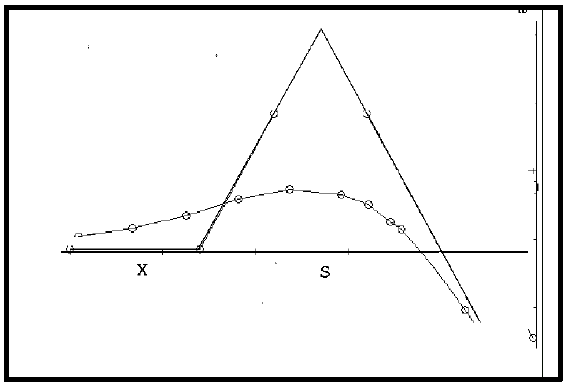

Let's take the call ratio spread as an example. The position normally has a profit graph of the shape as shown on the right. If you establish the position when the underlying futures contract, stock, or index is where the "X" is on the chart, then you can often sit back and watch the position develop without having to worry about price changes unless they get extreme. For example, if the underlying falls in price, you won't lose or make anything — you have merely tied up your capital. If it rises relatively slowly, and takes some time before it reaches the higher striking price ("S" on the graph), then you could easily have a profit by that time. The curved line on the chart shows where profits might lie at that time. In that case, you could just take your profit and be done with the position. The third scenario — quickly rising prices — is the one that would cause problems for the ratio spreader, and he would have to play defense to limit his losses before they became quite large.

The point is that the ratio spreader can maintain a relaxed demeanor until the underlying crosses through the upper striking price ("S"). This, then, is the advantage to the delta neutral strategy — it can buy a person time before decisions have to be made, and profits may accrue in the meantime.

Similar things can be said about the long straddle as well, although they occur in a reverse sort of way. If nothing happens when you own a long straddle, that's not good — although we usually recommend staying with the position for a while before giving up on it. For example, you might initially say that you'll risk 50% of the initial purchase price of the straddle. It would take some time before time decay eroded the straddle by half its value, but if it did, you would take your loss and go on to the next position. While a 50% loss is substantial, ideally you would have some very large profits in a few situations to offset those losses caused by time decay. Of course, if the underlying makes a big move in either direction, then you might have to trade the position with the trend, but at least you would be doing so from a profitable manner, hopefully. The key to our approach to the delta neutral strategy is not to just willy-nilly throw these delta neutral positions on all over the place, but to have a reason for establishing them. That reason would most likely be an aberration in volatility ("volatility trading"), perhaps coupled with a volatility skew that is in your favor — a situation often found in futures options in particular.

This article was originally published in The Option Strategist Newsletter Volume 6, No. 3 on February 6, 1997.

© 2023 The Option Strategist | McMillan Analysis Corporation