By Lawrence G. McMillan

This article was originally published in The Option Strategist Newsletter Volume 17, No. 11 on June 12, 2008.

In this article, we’re going to examine a popular strategy – the “collar.” We feel it’s apropos, since it appears that stocks may have now embarked on the next leg of the bear market. Moreover, we’ll give you our take on how to best utilize the strategy, and we’ll also take a look at a new application with $VIX options that should be of great interest.

Our long-term subscribers know that we like to use LEAPS options for collars, because – due to the way that options are priced, using a lognormal distribution – the longer-term options afford one the best chance to establish a no-cost collar with the greatest distance between the striking prices of the collar’s options. There are a lot of terms in the previous sentence, and some subscribers may not be familiar with them, so let’s review the basics of the strategy. Then we’ll move a little deeper into the nuances of follow-up action and new applications of collars.

The Collar: Basic Definitions

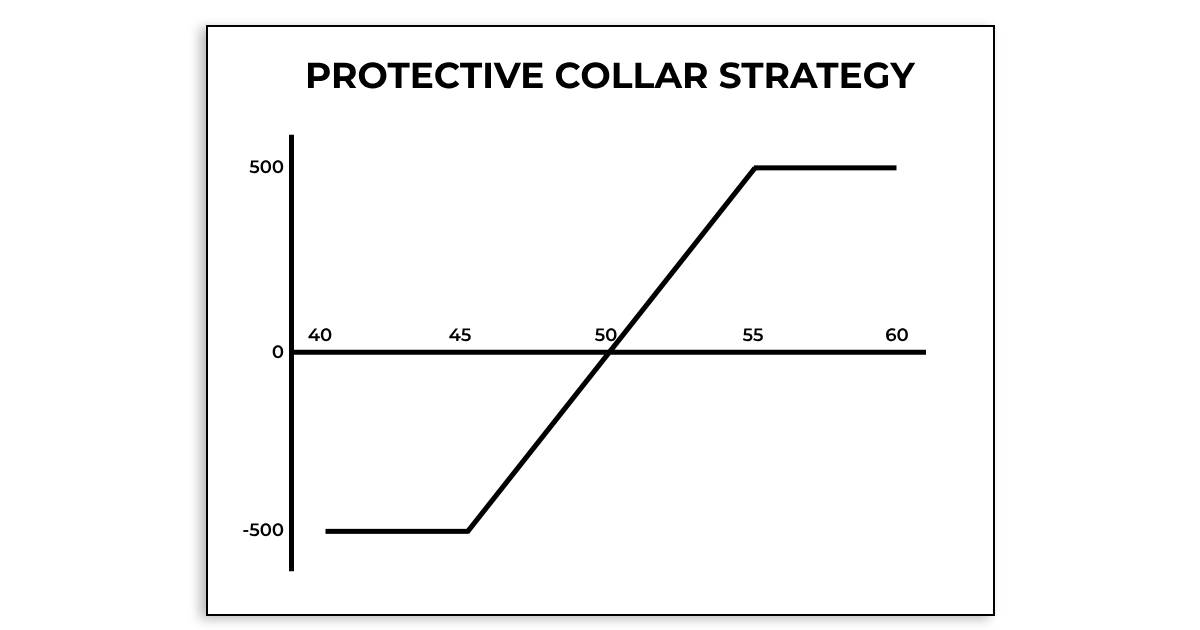

A collar is an option position that is overlaid on a stock or index position. It consists of buying a put (to limit downside risk) and selling a call (to help pay for the put). The sale of the call limits upside profit potential, though, so the resulting position is equivalent to a call bull spread, as shown in the figure on the right. Profits are limited above the strike of the written call, and losses are limited below the strike of the purchase put. In between, profits or losses are determined by movements of the underlying in between the two strikes.

A “zero-cost” collar is one in which the price of the put and the call are the same – i.e., one in which there is no cash outlay for the collar itself. One can predetermine his risk in a collar, by deciding how low of a put strike he wants to purchase. The distance between the current stock price and the put strike is that risk – a “deductible,” if you think of this like insurance.

With short-term options, if one desires a “zerocost” collar, it is likely that the put and call strikes can only be separated by a small distance. However, the longer the term of the options that are employed, the wider the distance between the put and call strikes can be, while still yielding a “zero-cost” collar.

Consider this example, using IBM prices from last July, 2007, shortly after the LEAPS options expiring in January 2010 had just been listed. At the time, IBM was at its highest price in over five years, and an investor who was concerned about IBM or the market in general might have figured it was time to look at collars as protection.

IBM:116.25

Jan('10) 100 put 8:00

Jan('10) 140 call 9.60

In this case, the investor would be willing to take about 14% downside risk – from the current price of 116.25 to the put’s strike at 100. With LEAPS options expiring in 2010, the cost of the put could be more than covered by selling a call with a striking price of 140. The all-time (adjusted) high for IBM in the bull market of 1999 was just below 140, so that seems like a reasonable upside strike for the collar. Using short-term options, one would never be able to get 40 points between the strikes.

Also, the higher the volatility of the underlying stock, the greater the distance that one can attain between the strikes in the collar. This example is one I’ve related before – both in this newsletter and in my seminars – but it is so outstanding that it’s worth mentioning again. In 2000, with Cisco (CSCO) trading at 130 ( it was a volatile stock then, with a volatility near 50%), a large corporate holder (5 million shares) was able to collar the position with 3-year options, over-the-counter. This holder – actually a listed company – established the “no-cost” collar: Buy 3-year puts with strike 130 Sold 3-year calls with strike 200!!

In other words, the put strike and the stock price were equal, so there was no downside risk. Meanwhile, because of the use of LEAPS and because it was a volatile stock, the call strike was over 50% higher than the current stock price. A tremendous protected position, to be sure!

The "Macro" Approach

If one has a portfolio whose performance tracks relatively closely with a broad-based index, one might be able to more efficiently hedge that portfolio with index option collars. Collars using $SPX options, for example, have characteristics similar to stock options, and thus LEAPS options work best.

In this example, priced at about the same time IBM was at 116.25 (previous example), one might have established a “macro” $SPX collar using these prices.

$SPX:1517

Dec('09)1450 put:107.6

Dec('09)1700 call:118.8

Here, the distance between the index price (1517) and the put strike (1450) is only about 4%, so the “deductible” is smaller. Furthermore, using the longest-term (Dec 2009) LEAPS, the call strike could be as high as 1700 and still produce a no-cost collar. Of course, if you overlaid this on a portfolio of stocks, you’d have to margin the Dec 1700 calls as naked short, but that could probably be done with the equity of the stocks in your portfolio.

The “macro” approach is less work, of course, since one only has to do one trade for his whole portfolio, as opposed to doing a whole series of collars on individual stocks. The drawback is that $SPX might not track that well with your portfolio of stocks, and so it might not provide the protection you thought it would. But, if your portfolio is truly diverse and broad-based, then an index collar might be a better choice.

A Small Problem With LEAPS

This year, there is a problem for an investor waiting for the new 2011 LEAPS to establish long-term collars with favorable distances between the strikes: their introduction is being delayed up to 4 months. The delay comes “after an analysis of quote traffic...in these series during the first four months of trading.” In other words, in the past, there hasn’t been “enough” volume during the first four months of trading of new LEAPS. This is not welcome news for those looking to establish LEAPS collars. If an investor wants to establish a LEAPS collar now, he must use 2010 LEAPS, which does not result in nearly as favorable of a spread between the options’ strikes as a 2011 LEAPS.

Using $VIX Options

We have previously written articles showing that a more dynamic approach to portfolio protection is to use $VIX options rather than $SPX options. When using $VIX options or futures as protection, one buys the $VIX derivatives against a long portfolio of stock holdings – for $VIX moves opposite to the broad stock market. Hence, a sharply falling stock market (and hence, your portfolio’s value) would be accompanied by a sharply rising $VIX. So owning $VIX futures or calls against a portion of your net assets would produce a dynamic hedge.

$VIX protection could be collared as well, although in this case, one would $VIX collar: Buy a $VIX call and Sell a $VIX put.

At the current time, here is a possible $VIX collar, using the longest-term options – November ‘08.

$VIX: 23.44 Buy $VIX Nov 35 call: 0.90 Sell $VIX Nov 20 put: 1.00

This is a no-cost collar but it represents too much risk to the stockholder. Here, the “deductible” would be the amount of money your portfolio would lose as $VIX rose from 23.44 to 35.00. That’s a long way and it could represent a significant loss.

More realistically, you’d want a collar that had a $VIX strike perhaps 4 or 5 points out of the money.

Buy $VIX Nov 28 call: 2.15 Sell $VIX Nov 20 put: 1.00

This is no longer a “no-cost” collar, but the premium from the put sale does help to offset the price of the $VIX calls that were bought.

Also, you may remember that we advised buying short-term $VIX calls as protection, for they more closely track the price of $VIX. Does that mean a short-term collar might work best? Consider the following collar:

$VIX: 23.44 Buy $VIX July 27.50 call: 1.50 Sell $VIX July 22.50 put: 1.85

This is a “no-cost” collar, but the strikes are very close together. If the market rallies, the $VIX put you sold could easily become an in-the-money put, thus capping off some of the upside gain in your portfolio. Still, this is not a terrible alternative. One might consider widening the $VIX July strikes to 20 and 30, which would cost a slight debit, but would be more in the nature of a pure protective strategy, with both options well out-of-the-money.

Adjusting The Collar?

What does one do with the collar once it’s in place? He could just leave it alone – planning on accepting the consequences, whatever they may be. That may not be the best approach.

Many investors will adjust the collar if the underlying declines in price. For example, consider the IBM collar on page 2. Suppose that after a while, IBM drops to 100 or slightly lower. The put in the collar is then in the money and will be selling for quite a bit more than the (then) deeply out-of-the-money call. Hence the existing collar could be removed for a nice credit.

What should one then do with the money? There are several choices: 1) Establish a new collar with lower strikes. If another “no-cost” is established, the upside strike will be even lower than before, so a strong rally by IBM might be limited. Most traders are reluctant to do this unless they’re fairly certain that the stock is headed lower (in which case, it would have been best to leave the original collar in place). 2) use the credits to buy some out-of-the-money puts. These puts will act as protection against further erosion in the stock price, while at the same time, the upside is no longer limited. 3) do nothing, leaving the stock “naked” long in the portfolio. This would normally be done only if one is fairly certain that the bottom has been made.

On the other hand, if the stock rallies after the collar has been established, the investor does not have an attractive array of choices. The call will have increased in price and the put will have decreased, so that it would require a debit to remove the collar. Of course, the stock will have increased as well, so overall the trader is ahead, just by not as much as he might have been had he not established the collar in the first place. Usually, a trader would only remove the collar during a rally if he is fairly certain that the worst was over, and the stock was heading higher. In the IBM example, that might occur if the stock broke out over 139 – the old all-time high.

Or, in a broader-based scenario, suppose that intermediate-term technical indicators such as put-call ratios and $VIX turned bullish; then a trader might remove collars figuring that he no longer needed the longer-term downside protection offered by the hedge.

Summary

Collars are an effective, low-cost way of protecting stock holdings. The “macro” approach is to use index collars – perhaps $VIX collars, while the “micro” approach is to establish collars on each individual stock in one’s portfolios. In either case, the use of LEAPS options produces a “no-cost” collar with the widest distance between the strikes. Later, adjustments to the collar may depend on one’s prognosis for stock price movements.

This article was originally published in The Option Strategist Newsletter Volume 17, No. 11 on June 12, 2008.

© 2023 The Option Strategist | McMillan Analysis Corporation