By Lawrence G. McMillan

This article was originally published in The Option Strategist Newsletter Volume 9, No. 16 on August 24, 2000.

It is somewhat common knowledge amongst option traders that the CBOE’s Volatility Index ($VIX) can be used as a predictor of forthcoming market movements. In particular, when volatility is trending to extremely low levels – as it is doing now – it generally means that the market is about to explode. In this article, we’ll put some “hard numbers” to that theory and we’ll also look at alternate measures of volatility (QQQ and the $OEX stocks themselves) to see what they have to say.

First, let’s give some background information for people not familiar with the concepts. $VIX measures the implied volatility of $OEX (S&P 100) Index options, which trade on the CBOE. For years, $OEX options had been the primary trading vehicle of speculators and hedgers interested in utilizing a broad market index. Lately, though, they have waned in popularity – partly due to the fact that individual stocks are so volatile. Still, the $VIX is watched as a measure of “market” volatility.

Using volatility as a predictor of stock prices means that one must use it as a contrary indicator. For example, when volatility spikes up to extreme highs, that normally occurs when the market is falling rapidly (even crashing). It is a sign of panic, and when $VIX reaches a peak in that case, it is usually a sign that everyone who is going to panic has already done so, therefore it’s time for the market to rally.

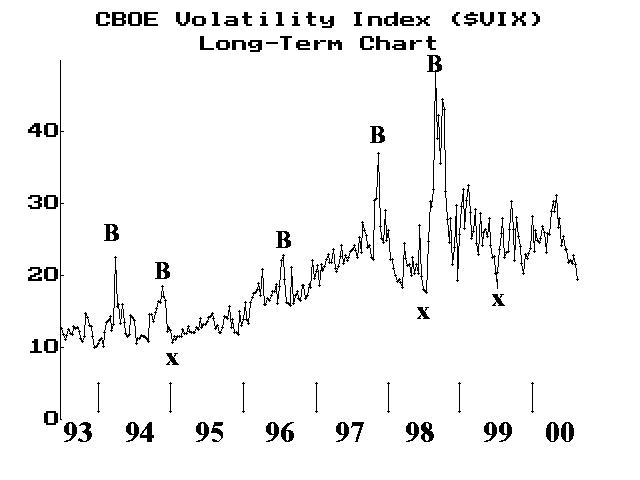

Observe Figure 1 below, which is a long-term (eight-year) chart of $VIX. There are a few buy signals (B’s) marked on the chart, illustrating the above point. In each of those cases, the stock market was plummeting rapidly and $VIX spiked up to a high level and fell back. Each time was a good time to buy the market for an intermediate-term rally.

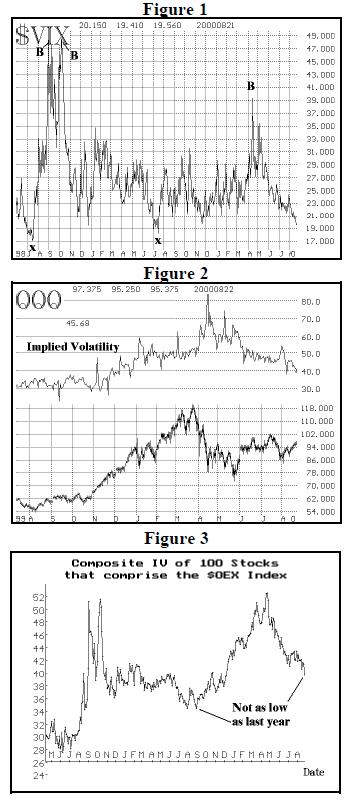

It is the opposite case that we must consider now, though, for implied volatility is drifting down to very low levels. This fact is especially evident from Figure 2 on the right, which shows the $VIX daily closes over the past two years or so. You can see that $VIX is currently at its lowest levels since July, 1999.

When $VIX reaches extremely low levels, it means that “everyone” is complacent. Option buyers are timid and option sellers are aggressive – for the same reason: no one expects much movement in the stock market over the life of the options. As with most things having to do with the stock market, when “everyone” agrees on something, the opposite usually occurs. In this case, that means that the market usually has an explosion.

Often, this explosion is to the downside – witness the two low readings in Figure 2 in July of both 1998 and 1999 (both are marked with an “x”). Those readings corresponded with significant high points in the market each year. Sometimes, however, the explosion occurs to the upside. Look once again at Figure 1. There are three “x’s”on that chart – the two from the last two years and one in early 1995. That 1995 “x” marked the beginning of an upside market explosion. It came after the Fed had finally stopped raising rates in 1994. Thus, if the Fed is truly done raising rates now, one could present an argument that we are in a similar environment to that of early 1995.

In any case, the point to be taken from these figures is that this is not a time to be “betting” on a stagnant market. Downside explosions usually occur rapidly. Upside “explosions” might take a little longer; in 1995, for example, the S&P 500 ($SPX) rallied from about 470 to 560 after that low $VIX reading, but it took five months to do so. That price rise was a very straight-line rise – following a tight channel all the way up. That is something that is typical of an “explosive” upside market move in the broad indices, for one cannot expect an index to “go parabolic” like an individual (internet) stock can.

But do all measures of volatility agree? We know that many traders who used to trade $OEX options now trade individual stock options or QQQ options. Figure 3 shows the current state of QQQ implied volatility overlaid on a chart of QQQ itself. The implied volatility of QQQ options is trending downward, but it has not reached the levels of even last fall. Thus, this doesn’t seem to be as extreme of a reading as $VIX is.

Finally, the last measure of broad market implied volatility that we like to use is shown on the bottom chart on the right. It is the composite implied volatility of the individual stocks that comprise the $OEX Index. This presents another view: Here, implied volatility is also trending lower but it has not reached the levels of last summer (1999). In fact, the lowest level on the chart was from the summer of 1998. This last chart, in my opinion, comes closer to agreeing with $VIX than one might first think. Even though its current readings are not as low as $VIX’s, they are still very low and therefore are warning of a market explosion, too.

Case Studies

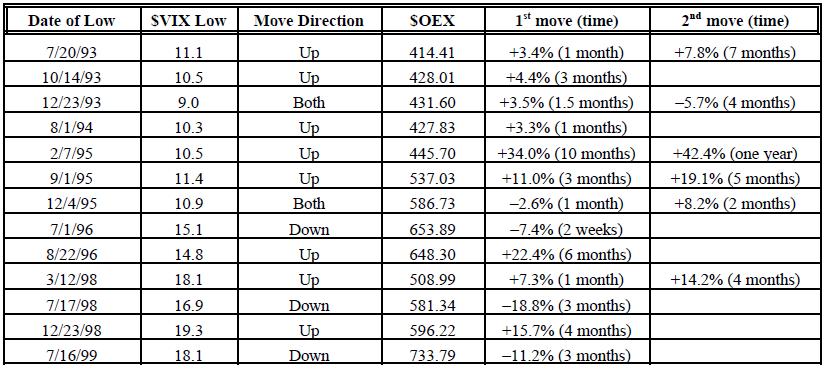

Everyone generally talks about low $VIX readings and what they mean, but I’m not sure I’ve ever seen a composite listing of the exact history of “low” $VIX readings. Therefore, we designed a study that found the cases where: 1) a $VIX reading was the lowest one for at least the past 90 days, and 2) the same $VIX reading was also the lowest one for at least 30 days going forward. In other words, these are our definitions of a “bottom” in the $VIX index. These two conditions for forming a “bottom” in $VIX have occurred simultaneously only 13 times since the beginning of 1993 – an average of about twice a year. However, one has not occurred since July, 1999 (over a year now). Currently, the first condition has been satisfied – any new lows in $VIX are the lowest readings in the past 90 days.

In the table at the bottom of this page, several items are displayed: the date of the low in $VIX, the $VIX level at that time, the subsequent direction of the market (up or down), the $OEX level at that time, and the extent of the move in percentage terms and how long it took. In certain cases, there are two moves listed, for after the first move took place, another followed quickly. In some cases, the two moves were in opposite directions, which is when “both” is listed for the move’s direction.

Even if one only concentrates on the first move that took place, it can be seen that there was plenty of room for profits for straddle buyers. The moves listed are the maximum moves that took place.

To gauge how profitable a straddle buy might be, one can use these rules of thumb: at a volatility of 12%, a three-month straddle costs about 4.3% of the stock price. At a volatility of 18%, a three-month straddle costs about 7% of the stock price. With those figures in mind, it is easy to see that the moves in the table were generally big enough to produce a profit from a straddle buy in $OEX.

It is also interesting to note in how many of the thirteen cases the market moved up after a low $VIX reading was established. That is, the market move that followed was on the upside. This generally flies in the face of “conventional” wisdom about a low $VIX reading. That is, most people say that a low $VIX reading means the market is topping out. The data proves otherwise, although what is probably behind this thinking is that the three major declines (1996, 1998, and 1999) all started from low $VIX readings in July.

Prognostication

Now that we have “survived” July, 2000, does that mean the explosion will be on the upside? That is certainly a possibility. The put-call ratios are still relatively high on their charts, and are probably not far from setting up buy signals. It seems like the market has been going up for quite some time, since the big-cap indices have been doing so since very late July. NASDAQ indices have not been as strong.

Currently, the following big-cap indices’ options are trading at the indicated percentile of implied volatility: $OEX: 4th percentile $SPX: 8th percentile SPU (S&P Sept futures): 3rd percentile So, straddle purchases in any of these would be reasonable. However, we don’t want to buy volatility until it shows signs of firmly establishing a bottom. It seems unlikely, but what if $VIX were to decline to 16? Or 14? We don’t want to buy index option volatility until we at least see a temporary bottom in $VIX. So, we’ll use an approach that we’ve used in the past. In order to keep total expenses down, this recommendation will utilize Dow- Jones ($DJX) options, but if you have the capital available, $OEX or SPU options would be slightly better choices because of liquidity reasons.

This article was originally published in The Option Strategist Newsletter Volume 9, No. 16 on August 24, 2000.

© 2023 The Option Strategist | McMillan Analysis Corporation