By Lawrence G. McMillan

This article was originally published in The Option Strategist Newsletter Volume 2, No. 15 on August 12, 1993.

Both the metals and the grains have been extremely volatile lately. Their price action provides the backdrop for discussion of an important topic: how does the neutral strategist handle volatile market moves, especially when his positions contain naked options? The attractiveness of neutral trading or hedged strategies is that one is not exposed to short-term market moves in general. However, when markets make large moves, either quickly or over time, the neutral position takes on a much riskier tone. The strategist will generally attempt to make an adjustment at that time, either to minimize risk or at least to return the position to a neutral state.

Let's begin by looking at neutral positions that have naked options in them. These would include ratio writes, ratio spreads, and selling combinations. The first ironclad rule that one must follow is to have a plan of follow-up action that is set forth when the position is first established. You must set strict action points, based on the risk of the position.

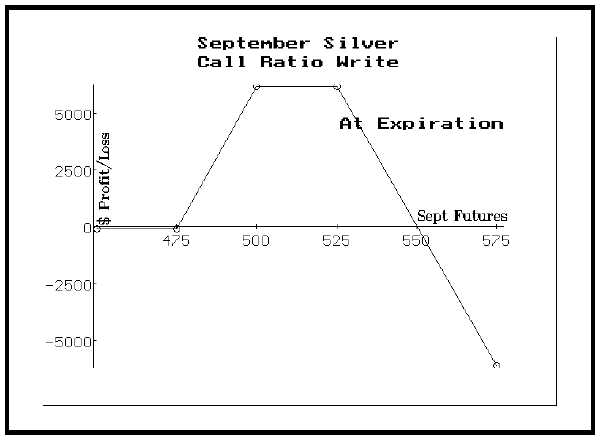

To illustrate these concepts, we'll use our current position F41, which is a ratio call spread in September Silver futures options. Silver traded to the upside while we had this position in place, but then fell — very quickly — back to the downside. The chronology of this position is a good example of the various things that can happen. Originally, this position was long 5 Sept 475 calls, short 5 Sept 500 calls, and short 5 Sept 525 calls. The initial position was established at approximately 0 debit, so there was no risk to the downside, and the upside breakeven point was 550, above which there was theoretically unlimited risk. The initial profit potential at expiration is shown on the right.

As time passed and expiration drew near, we set the defensive posture to be one of attempting to prevent large losses, while allowing Silver to roam within the profitable range. So we decided to only take action if silver traded at 540, at which point we had a stop order to buy 2 futures; in addition, we placed a stop to buy 3 more at 550 to completely cover the short calls with long futures if Silver were to trade up that far. One should generally try to set his ultimate (last) defensive action point at or just outside the profit area, figuring that he should be willing to lose a little money in order to keep the profit range wide as possible for as long as possible. If one "squeezes" his defensive action points too close to the initial stock price, then he may have to make more adjustments than are necessary, which reduces the overall profitability and also involves increased commissions costs.

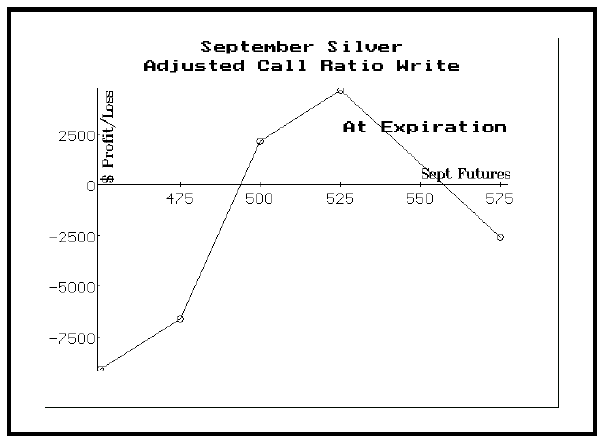

Silver did indeed rally through 540 (but never 550), so we bought 2 futures against our net short of 5 calls at that time. This defensive action changed the position so that the profit picture at expiration was as shown on the right. Whenever one takes defensive action, he must once again install new follow-up action points to account for the change in profit potential that has occurred. If one had merely bought the 2 futures and not thought about where he would sell them if Silver subsequently fell in price, he would be remiss in his handling of the position. When the buy stop of 2 futures was elected, we immediately followed up by placing a sell stop for these 2 futures at 515. In other words, even though silver was rising, we needed to be prepared to re-adjust the position if Silver turned around and headed down instead. The neutral strategist does not normally attempt to predict the market; he merely wants to be prepared to react to it. The reason we chose 515 as the stop point was that 515 is near the middle of the maximum profit area of the graph on the right.

Last Thursday was the day of the great collapse in the metals (see the Futures Option Section for further comments on that). Silver opened at 521 and traded down through 515 almost immediately. It then proceeded to fall all the way to 478 that day. Fortunately, we had our sell stop in place. Even though the defensive action did cost some money, it left the position with the possibility of still being able to make money, although not as much as the original position. The sell stop at 515 kept the loss on the adjustment to a reasonable amount: the position is still able to make money if September Silver is above 485 at expiration.

In positions involving naked options, defensive actions invariably involve taking realized losses against the overall position. Thus, the fewer defensive adjustments that one can make, and still feel comfortable with the risk, the better. Most neutral positions can withstand one or two adjustments that result in realized losses against the overall position, but more than that will normally make the entire position a loser. These points can be seen from our Silver position, in which 2 futures were bought at 540, but then had to be sold at 515 in order to return the position to a neutral status. However this one adjustment and its accompanying loss did not destroy the entire position. There was still opportunity to make money as long as Silver was between 485 and 540 at expiration. The adjustment that was made involved taking a loss, but the overall position still retains profit potential. The purchase of the 2 futures was necessary at the time Silver was rising, because the neutral strategist did not know if Silver was going to continue higher or not. If it had, the entire position would have been exposed to a large loss if no defensive action were taken.

Hedging With Stock Versus Covering Short Options

One of the dilemmas that a neutral strategist faces in positions involving naked options is how to approach defensive action. Should he cover the short options (and thus probably pay some time value premium) or should he use the underlying as the vehicle for adjustment? The answer is not always an easy one, but as with most decisions that the neutral strategist makes, it deals with probabilities.

When Silver traded at 540, we could have either bought back some of our short September 525 calls or we could have bought futures to convert them into covered calls. Obviously, if the calls were bought, there would be an additional expense of time value premium plus the spread between bid and offer, which can be relatively large on in-the-money calls. On the other hand, the purchase of futures costs no time value premium and the spread between bid and offer is tighter. So the purchase of futures is less costly, as long as the futures don't reverse and fall back below the striking price of the call. Thus the key as to whether to buy futures or to buy the calls hinges on one's assessment of the probabilities of Silver reversing from 540 and falling below 525. We felt that with only two weeks remaining until expiration, it was "safe" to buy the futures. Thus when Silver traded at 540, we bought futures since the short time remaining until expiration mitigated the possibility of Silver whipsawing and falling back below the 525 strike. Unfortunately, it didn't eliminate the possibility, and Silver did indeed fall below the 525 strike.

In retrospect, it would have been better to buy the 525 calls as a closing transaction, rather than to buy the futures. However, the original decision was made utilizing probabilities, not certainties, and the decision to buy the futures was probably the better choice at the time. This just shows once again that there are no guarantees in the markets. If the same situation occurred many times, it would generally be better to buy the futures, but in this one case it

As a general rule, one would adjust with options when there is a significant probability that the underlying security could reverse direction and trade back through the striking price of the option. This would normally occur when there is still a reasonably large amount of time remaining until expiration. The corollary to this guideline is that one normally hedges with the underlying security itself as expiration draws near. These are general guidelines of course, and individual circumstances may sometimes dictate the opposite course of action. The key is always to attempt to assess the probabilities of the underlying reversing direction and trading back to the striking price of the options. If one feels that there is a rather large chance of that happening, then he should adjust by buying the short options back in a closing transaction. Conversely, if he feels there is only a low probability, then he should adjust with the underlying security itself (unless there is virtually no time value premium in the options).

This article was originally published in The Option Strategist Newsletter Volume 2, No. 15 on August 12, 1993.

© 2023 The Option Strategist | McMillan Analysis Corporation