By Lawrence G. McMillan

This article was originally published in The Option Strategist Newsletter Volume 1, No. 22 on November 12, 1992.

In the last issue, we looked at some of the rewards and pitfalls of calendar spreads using index or equity options. This week, we'll take a look at the calendar spread using futures options.

A calendar spread using futures options is constructed in the familiar manner -- buy the May call, sell the March call with the same striking price, for example. However, there is a major difference between the futures option calendar spread and the stock option calendar spread. The difference is that a calendar spread using futures options involves two separate underlying instruments while a calendar spread using stock options does not. When one buys the May soybean 600 call and sells the March soybean 600 call, he is buying a call on the May soybean futures contract and selling a call on the March soybean futures contract. Thus the futures option calendar spread involves two separate, but related, underlying futures contracts. However, if one buys the IBM May 100 call and sells the IBM March 100 call, both calls are on the same underlying instrument -- IBM. This is a major difference between the two strategies, although each is called "calendar spread".

To the stock option trader who is used to visualizing calendar spreads, the futures option variety may confound him at first. For example, a stock option trader may feel that if he can buy a four-month call for 5 points and sell a two-month call for 3 points, that he has a good calendar spread possibility. Such an analysis is meaningless with futures options. If one can buy the May soybean 600 call for 5 and sell the March soybean 600 call for 3, is that a good spread or not? It's impossible to tell, unless you know the relationship between May and March soybean futures contracts. Thus in order to analyze the futures option calendar spread, one must not only analyze the options' relationship but the two futures contracts' relationship as well. Simply stated, when one establishes a futures option calendar spread, he is not only spreading time -- as he does with stock options -- he is also spreading the relationship between the underlying futures.

Example: A trader notices that near-term options in soybeans are relatively more expensive than longer-term options. He thinks a calendar spread might make sense as he can sell the overpriced near-term calls and buy the relatively cheaper longer-term calls. This is a good situation considering the theoretical value of the options involved. He establishes the spread at the following prices: Soybean Initial Price Trading Contract Position March 600 call 14 Sell 1 May 600 call 21 Buy 1 March future 594 none May futures 598 none

The May/March 600 call calendar spread is established for 7 points debit. March expiration is two months away. At the current time, the May futures are trading at a four point premium to March futures. The spreader figures that if March futures are approximately unchanged at expiration of the March options, he should profit handsomely because the March calls are slightly overpriced at the current time, plus they will decay at a faster rate than the May calls over the next two months.

Suppose that he is correct and March futures are unchanged at expiration of the March futures. This is still no guarantee of profit, because one must also determine where May futures will be trading. If the spread between May and March futures behaves poorly (May declines with respect to March), then he might still lose money. Look at the following table to see how the futures spread between March and May futures affects the profitability of the calendar spread. The calendar spread cost 7 debit when the futures spread was initially: March 4 points under May.

Futures Prices Futures May 600 call Calendar

March/May Spread Price Spread

Price Pft/Loss

594/570 March 24 over May 4 -3

594/580 March 14 over May 6½ -½

594/590 March 4 over May 10 +3

594/600 March 6 under May 14½ +7½

594/610 March 16 under May 22½ +15½

Thus, the calendar spread could lose money even with March futures unchanged -- top two lines of table. It also could do better than expected if the futures spread widens -- bottom line of table.

The profitability of the calendar spread is heavily linked to the futures spread price. In the above example it was possible to lose money even though the March futures contract was unchanged in price from the time the calendar spread was initially established. This would never happen with stock options. If one established a calendar spread in IBM and the stock were unchanged at the expiration of the near-term option, the spread would make money virtually all of the time.

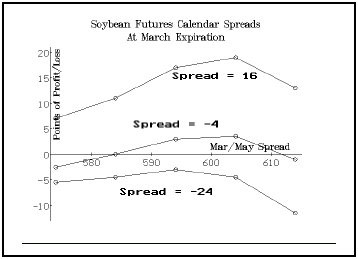

The futures option calendar spreader is therefore trading two spreads at once. The first one has to do with the relative pricing differentials (implied volatilities, for example) of the two options in question, as well as the passage of time. The second one is the relationship between the two underlying futures contracts. As a result, it is difficult to draw the ordinary profit picture. Rather one must draw a series of profit pictures that show the option spread results at various value of the futures spread. The profit graph below shows how this approach looks: the above example spread's profits are shown for three different value of the March/May futures spread at March expiration. Several general conclusions can be made about the profitability of the futures option calendar spread. First, if the futures spread improves in price, the calendar spread will generally make money. This is the top curve on the graph in which the March/May spread widened from its original value of March trading 4 points under May to where March is trading 16 points under May. Second, if the futures spread behaves miserably, the calendar spread will almost certainly lose money (bottom line of graph, where the future spread collapsed from March 4 points under to a horrendous level of 24 points over!). Third, if March futures rally and the futures spread worsens, one could lose more than his initial debit (bottom right-hand point on graph). This is partly due to the fact that one is buying the March options back at a loss if March futures rally, and may also be forced to sell his May options out at a loss if May futures have fallen at the same time. Fourth, as might be expected, good results are obtained if March futures rally slightly or remain unchanged and the futures spread also remains relatively unchanged (middle curve on graph).

This example demonstrates just how powerful the influence of the futures spread is. The calendar spread profit is predominantly a function of the futures spread price. Thus, even though the calendar spread was attractive from the theoretical viewpoint of the option's prices, its result may not reflect that theoretical advantage, due to the influence of the futures spread. Another important point for the calendar spreader used to dealing with stock options to remember is that one can lose more than his initial debit in a futures calendar spread if the spread between the underlying futures inverts.

A Substitute For The Intramarket Spread

Recall that an intramarket spread in futures involves two different contracts on the same underlying commodity -- for example, long May soybeans and short March soybeans. The futures option calendar spread can be thought of as a substitute for this type of spread, especially when both options are in-the-money. If the options are statistically attractive (that is, one is selling an option that is expensive relative to the one he is buying), then the calendar spread generally outperforms the intramarket spread. This, then, is where the true theoretical advantage of the calendar spread comes in. So, if one is thinking of establishing an intramarket spread, he should check out the calendar spread in the futures options first. For if the options have a theoretical pricing advantage, the calendar spread may outperform the standard intramarket spread.

In summary, the futures option calendar spread is more complicated when compared to the simpler stock or index option calendar spread. As a result, calendar spreading with futures options is a less popular strategy than its stock option counterpart. However, this does not mean that the strategist should overlook this strategy. As the strategist knows, he can often find the best opportunities in seemingly complex situations because there may be pricing inefficiencies present. For this strategy, its main application may be for the intramarket spreader who also understands the usage of options.

This article was originally published in The Option Strategist Newsletter Volume 1, No. 22 on November 12, 1992.

© 2023 The Option Strategist | McMillan Analysis Corporation