By Lawrence G. McMillan

This article was originally published in The Option Strategist Newsletter Volume 23, No. 22 on December 1, 2014.

With the stock market at all-time highs, and many stock holders sitting on large gains, thoughts often turn to options as a hedging technique. For stock owners, there are two ways to provide protection to a portfolio: 1) macro protection, which involves the use of index options to hedge an entire portfolio’s risk, or 2) micro protection, which involves the use of individual options on each stock in the portfolio. In either case, the use of a collar is often attractive to the owner of the portfolio, because it is often established for zero debit.

However, whenever one hedges a portfolio – or anything, for that matter – he must give up something in the process. If he eliminates downside risk, he likely relinquishes some upside profit potential, for example. That is certainly the case with collars.

In this article, though, we’re going to look at a type of collar which might allow one to “have his cake and eat it too.” That is, the downside will be protected, but there will still be upside profit potential. We have addressed the topic of collars in many past issues.

Definitions

Let’s begin with the basic definitions, so that this article can stand on its own if someone is trying to understand the concepts. A collar consists of both buying a put and selling a call on the same underlying instrument. Typically, the put and call have the same expiration date, but different striking prices, but that is not a requirement.

Usually, the options are established with strikes that are out-of-the-money. If possible, a “no-cost” collar is established by selling a call with a price greater than that of the put being purchased. In that way, the stock owner does not have to lay out any cash for the collar.

Example: An example of a collar on 100 shares of stock (Implied vol = 25%): XYZ: 50 Buy 1 April 45 put @ 1.05 Sell 1 April 55 call @ 1.40

Once the collar is in place, the stock owner’s risk is limited to the strike of the put. In this example, if XYZ falls below 45, there is no further risk because the ownership of the put protects the stock at all lower prices.

The use of an out-of-the-money put means that one will have some risk in the position. If one thinks of this as “insurance,” he could consider that risk as the deductible portion of this insurance. In other words, if the stock market collapses, he will lose the deductible, but nothing more.

Furthermore, there is limited profit potential. Since a call has been sold with a striking price of 55, the profit potential is limited to that price (unless the call is bought back). This is the tradeoff: one has acquired a “no-cost” hedge for his stock and limited downside risk to 5 points (from 50 down to 45), but in return he has given up the potential for any gains beyond 55.

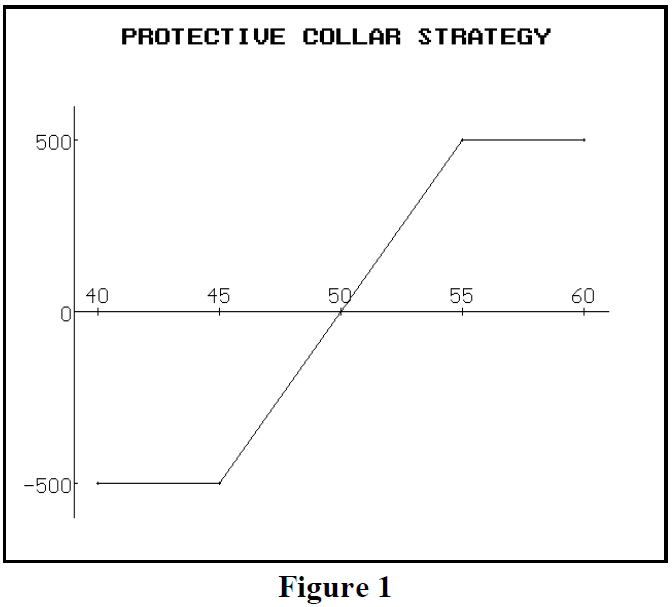

In between 45 and 55, the position’s gains or losses depend on the oscillations of the stock price in that range. Figure 1 shows the profit graph of this example.

Without getting into a complete analysis of collars, suffice it to say that the more volatile the underlying, and the smaller its dividend, the farther apart one will be able to split the strikes between the put and the call in order to attain a no-cost collar. One can often increase his opportunities for wider strikes in a no-cost collar by utilizing the longest- term options available. Listed options have a maximum life of a little less than three years, but most of the time options of that length are not available.

“Macro” Collar Strategies

One could construct a collar with index options that would hedge his entire portfolio. For example, suppose that one had a $1 million portfolio that behaved more or less like the S&P 500 index, and he wanted to create a macro collar.

He could buy out of the money $SPX puts and sell out of the money $SPX calls. Technically, he would have to do this in a margin account and use the equity loan value of his stock portfolio as collateral for selling the $SPX calls. That’s because his broker will consider the calls as having been sold naked; there is no crossmargining between a portfolio of long stocks versus short $SPX calls (even though it is a logical hedge).

The risk here is that one’s portfolio might not perform exactly like the S&P 500 Index, but if one has a portfolio of large-cap stocks, the differences in performance will likely be small, and the hedge should provide the desired benefits of limited downside risk at little or no outlay for the protective collar.

Example: suppose that one wants to hedge his $1 million $SPX-like portfolio. Currently $SPX is trading at 2070. Furthermore, suppose that he is willing to risk 15% as his “deductible.” Then the strike would be placed at 0.85 * 2070 = 1759.50, or 1750 for practical purposes (the closest strikes are 1750 and 1775). At current prices, this collar is available: Buy $SPX Dec (2016) 1750 put: 115.50 Sell $SPX Dec (2016) 2200 call: 120.70

Thus the call would be about 6.3% out of the money, so that much profit potential would remain to the upside. If volatility were higher, then it would be possible to sell a higher strike and still establish the no-cost collar.

In this example, one would buy 5 collars. That number is determined in this manner:

15% risk means the portfolio would theoretically be worth $850,000 when the lower strike is reached. So $850,000 / (1750 * 100) = 4.86.

Alternative Collar Strategies

Most stock owners do not like to limit the upside for their stocks. That is why covered call writing has been such a despised strategy in this long-running bull market. Premiums are low since volatility is low, but stocks keep getting called away (or calls have to be bought back for large debits) since the stock market keeps rallying.

Thus it would seem that a collar is no longer appropriate in such situations. However, there are two modifications that can be made that may help overcome at least part of this problem.

Extraction: the first strategy is one that can be used by any covered writer when his stock is about to be called away. It should be noted that a call should not logically be assigned unless all of its time value premium has disappeared. What can cause the time value premium of an in-the-money call to disappear? Only two things: expiration, or an impending dividend payment. Thus, if one is selling covered calls – either as a strategy in its own right or as part of a collar – he needs to have a warning calendar telling him when his stocks are going to go exdividend.

On the day before the stock is above to go exdividend, if the written call is bid at or below parity, then it is definitely liable to be assigned. However, if the call is bid above parity, then it would be a mistake for the call holder to exercise. Do call holders sometimes make mistakes and exercise calls they shouldn’t – thus causing call writers to get assigned? Yes, but rarely.

In any case, once one determines that his stock is about to be called away, he needs to decide if he wants to let that happen or not. If he wants to keep at least some of the stock, then an extraction might be useful.

In an extraction, one buys back all of his written calls and sells off a small portion of his stock in order to fund the buyback of the calls.

Example: assume that owns 3,000 XYZ, and it is trading at 50. He had written 30 Dec 45 calls against the stock some time ago, but now they are about to be assigned, since XYZ is going exdividend tomorrow. The calls are trading at 5, since they have no time value premium remaining. He could: Buy back 30 calls @ 5 = $15,000 debit and Sell 300 XYZ @ 50 = $15,000 credit Thus he would not have to reach into his pocket to exit the calls. He would then be left with 2,700 shares of stock. At that point, he could continue, and write 27 out-of-the-money XYZ calls if he wishes. Or he could say, “I’m never getting in that bind again,” and swear off covered writing altogether. In any case, he has extracted himself from the dilemma of losing his stock or haviung to buy back the calls for a big debit to keep all of his stock. He might even find that he “sold high,” since this stock has obviously been rallying.

The tax ramifications are not severe, either. The buyback of the calls creates a short-term loss (assuming they were sold for something less than 5). The sale of the stock creates a capital gain, but the loss on the calls will offset part – or maybe even most – of it.

This is a strategy that many more covered writers should employ, rather than just paying debits to buy back deeply in-the-money calls in order to hold onto long stock deep in a bull market.

Partial Collar: the other strategy that one might employ is the partial collar. This is done when the collar is established. Returning to the first example on page 2, suppose that these prices exist:

XYZ: 50 April 45 put: 1.05 April 52.5 call: 2.15 April 55 call: 1.41

Suppose that one owns 3,000 shares. He could set up the simple collar shown on page two (Apr 45 put vs. Apr 55 call, in equal quantities), or he could try this partial collar:

Buy 30 April 45 puts @ 1.05 = $3,150 debit Sell 15 April 52.5 calls @ 2.15 = $3,225 credit

Thus a no-cost collar has been established, providing full protection of 30 puts for the 3,000 shares at a price of 45, as before. But now the upside is only capped on 1,500 shares. The other 1,500 shares are free to roam as high as they can go. Yes, the profit potential on the capped 1,500 shares is less (52.5) than it would be with the “normal” collar (55), but many enjoy the thought that the upside is unlimited on a good portion of their shares.

So, be creative with your collar strategies. You may find that you can provide protection and still feel good about achieving further upside profit potential.

This article was originally published in The Option Strategist Newsletter Volume 23, No. 22 on December 1, 2014.

© 2023 The Option Strategist | McMillan Analysis Corporation