By Lawrence G. McMillan

This article was originally published in The Option Strategist Newsletter Volume 18, No. 4-5 on March 5, 2009.

I’m a numbers guy – degrees in math and all that – so I get a lot out of looking at charts, tables, and so forth that show past market behavior. That also makes me a technician. But it always amazes me how people can look at the same set of data and come away with very different conclusions.

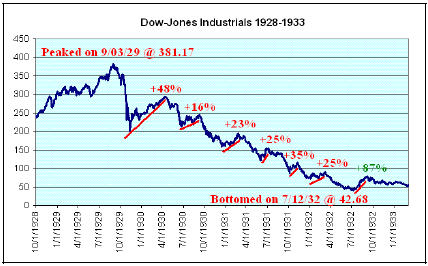

Consider the chart below. It is the Great Depression bear market – from its peak in September of 1929 to its eventual bottom in July of 1932. You probably didn’t know it bottomed in July, did you? I read only recently that it bottomed in March of 1933. But it didn’t. The first really strong rally occurred in March of 1933, but the actual bottom was July, 1932 at Dow 42.68. (As an aside, why wouldn’t you buy Dow 42? What more could you possibly be waiting for on the downside?).

Another important fact about bear markets in general and about the 1929-1933 market in particular, is that relatively large percentage rallies can spring up. The first, and perhaps most famous one, was the nearly 50% rally off the 1929 bottom into April of 1930. Most traders at the time thought the bottom was in and everything was fine. Some stocks – AT&T, for one – even traded at new all-time highs on that rally.

Then there was a retest of that bottom in June of 1930. But once that low gave way, the rout was on. Yes, there were four more rallies of 25% or more until rock bottom was hit in July of 1932. In fact, I have heard and seen perma-bulls on TV citing the fact that there were these big rallies during the Great Bear Market. Well, if you think you could have successfully traded those, you’ d probably be very wrong. Knowing how these perma-bulls work, they were probably buying all the way down, and when they got those rallies, they crowed about them, but in the final analysis they got wiped out.1

Finally, there was a much bigger rally (87% in two months) off the actual lows in 1932. Perhaps the size of that rally was the warning sign to the bears that the bear market was over.

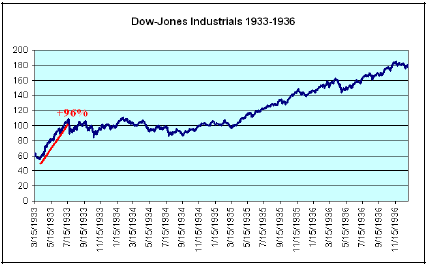

The second chart shows the start of the bull market that we are still in today (okay, that’s a bit of a stretch, but the markets never made another lower low after July, 1932). Franklin Roosevelt wasn’t inaugurated until March 4, 1933 (up until that time in history, the new President had always been inaugurated on March 4th of the year following the election; but after 1933, the inauguration date moved to January 20th).

The top chart ends with trade date March 3, 1933. The bottom chart begins with trade date March 15, 1933. There is no missing data, however, since the NYSE was closed for that period. Roosevelt was inaugurated on Saturday, March 4, 1933, and he declared a banking holiday on March 5th. The NYSE was closed from March 6th through March 14th, 1933.

As soon as the markets reopened, the Dow gapped higher by over 10%, sat around for a week or so, and then rose 96% over the next four months (as marked on chart). That rally generated so much volume that the NYSE had to routinely close on Saturdays during the summer of 1933 to catch up with the paperwork.

Does this data relate well to today’s market? Not exactly, of course – no two markets are complete repeats of each other. But there are parallels. The rally that rose off the November 2008 bottom was roughly 27%, ending in early January 2009. So, it wasn’t anywhere near as powerful as the 48% 1929-1930 rally (I’ll present other scenarios shortly).

Moreover, once $SPX retraced to the November 2008 lows (740 on $SPX) last month, there was only a rally of a few days, before prices gave way to new lows – and the rout was on. That part is the same: once the lows that “everyone” thought marked the bottom give way, there is massive selling. We are still seeing that now.

Another Viewpoint

As longer-term subscribers know, I have long said that there would be a series of three bear markets – much as there were in 1966, 1969-70, and 1973-74. Those bear markets purged the system of all its excesses. Each was more severe than its predecessor The 1974 bottom was made on low volume, and few participants were left. I fully feel that this bear cycle will end the same way. In between those bears, the Dow rose back to its highs each time (near 1,000).

Currently, the conventional view is to say that 2000-2002 was a bear market, with the Dow recovering all those losses in between, and now we are in the second bear market. Could we possibly see the Dow rally all the way back to its highs before a third bear market takes place? I don’t really believe so.

Rather, we need to realize that the 1998 market correction (the Russian Debt Crisis and the Long-Term Capital Crisis) was actually a small bear market. Intraday, the averages did decline by 20%, so it qualifies. This is quite similar to the 1966 bear market, which saw the Dow decline by about 25%.

Viewing 1998 as a bear market is not a lone opinion. John Bollinger has said all along that he feels the market peaked in 1998, and the clock has been ticking ever since. So, from that perspective, we are now in the third and final bear market in this cycle. There is likely plenty of bear still to come, and there won’t be any rallies back to the highs. When this one ends, people won’t want to have anything to do with stocks – just as was the case in 1932 and 1974.

Here’s another interesting view, too. Louise Yamada – a respected technician – was on TV the other day. She pointed out that the 2000-2002 bear market can be viewed as the modern equivalent of the “Crash of ‘29,” a 50% loss. Then the 2003-2007 bull market, manufactured by low interest rates and easy money, was the super-charged modern equivalent of the big 50% rally that took place in 1929-1930. And now that we have broken down below the 2002 lows, we are in the stages of the 1930-1933 bear market. I’m not sure I agree with this thesis, because the time frames and price moves are just so different, but it’s certainly unique thinking.

This article was originally published in The Option Strategist Newsletter Volume 18, No. 4-5 on March 5, 2009.

© 2023 The Option Strategist | McMillan Analysis Corporation