By Lawrence G. McMillan

This article was originally published in The Option Strategist Newsletter Volume 18, No. 13 on July 10, 2009.

Everyone enjoys a good speculation now and then – even the most confirmed hedged trader. However, there are a lot of ways to handle a speculative position once it’s in place. In this article, the main focus is going to be on when and where to take profits – as opposed to cutting losses. We’re going to look at several partial profit strategies in an attempt to show what one is really doing to his position in the name of taking profits.

However, it should be stated up front that nearly every speculative position – and most hedged positions, too – should have a protective stop in place when they are first established. The placement of such stops is not the main subject of this article, but suffice it to say that we place our protective stops based on the stock price – not the option price. That’s because an option is a derivative security, and often a relatively illiquid one at that, when compared to the underlying stock. Hence, it’s the movements of the underlying that are important to the profitability of the position. This is especially true if the option is in-the-money when purchased, as ours normally are. Thus, we feel a stop should be placed using the chart patterns of the underlying instrument, and not some fixed percentage of the option price, for example.

The Philosophy of Profits

But what we really want to discuss here is how to handle profitable positions. There are different schools of thought as to how to treat a profitable speculative position. They generally fall into these three categories. 1) average up 2) use targets 3) use a trailing stop

Averaging up: Many stock and option traders are not familiar with averaging up. It is more of a futures strategy, where traders press their bets in a winning position, hoping to maximize momentum in a highly leveraged situation. Obviously, small corrections after one has averaged up can wipe out the entire profit of a position. Hence, it is not a strategy that we endorse for normal trading, although it has proven to be successful in trading contests. It is akin to a baseball player trying to hit a home run every time up, or else making an out.

Using Targets: in this approach, one sets a target for a trade and exits the trade if the target price is reached. The target can be based on percentage profits or perhaps on chart patterns. No matter how it is based, though, one limits the profitability of his trade. Thus, one will never have a huge gain in any one position. Our approach is much more towards “let your profits run” Supposedly, using targets while trying for limited profits is intended to increase one’s rate of profitability in trading. However, there is no real evidence to support that. Moreover, if there is never a large profit to offset several losses, the overall return of the strategy suffers.

Using the baseball analogy again, this is like a baseball player only hitting singles, and never trying for a home run. Or to put it the way Babe Ruth did, when denigrating Ty Cobb’s style of play: “If I’d just tried for them dinky singles, I could’ve batted around six hundred.” Hence we most certainly do not endorse the approach of using targets.

Using Trailing Stops

The rest of this article will discuss the various nuances of using trailing stops in a profitable speculative trade. This will encompass related strategies, such as taking partial profits and rolling calls up (or puts down). Some of this initial discussion – setting and using trailing stops – has been covered in this newsletter before, but the remainder of the article has not. We have repeated this information for completeness, as this is a discussion of the entire methodology of handling profits in a speculative trade.

Setting The Trailing Stop

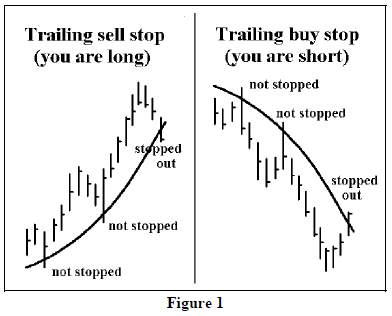

A trailing stop is merely a moving average that trails along below a profitable long position as the stock continues to rise (conversely, a trailing stop can also be a moving average that trails along above a profitable short position – or long put position – as the stock continues to decline). One stays in the position as long as the stock has not violated the trailing stop. There have been cases where a futures contract has remained in a trend for many months, during which time large profits build up. While stocks don’t trend as well as futures, they too can trend for a long time. The use of trailing stops allows one to capture the large profits available in such a trend.

“They” always say it’s hard to cut your losses and let your profits run. That is not true, in my opinion. If you set a reasonable stop to begin with – or even just buy an option as your initial speculative position – you have limited your losses. Then, if you use trailing stops, you can easily let your profits run.

Closing Stops

Figure 1 shows an example of the use of trailing stops. In this graph – as in our actual trading and recommendations – we use mental closing stops. That is, one is not stopped out unless the stock closes through the stop (merely trading through the stop intraday is not sufficient for exiting the position).

Obviously, this mental stop order can’t be placed with your broker or brokerage firm. You have to get involved yourself, as a trader, to implement it.

In practical terms, this means that if you are sitting in front of a trading screen as the market is nearing the closing bell (4pm, Eastern time), then you look at the stock underlying your option position. If the stock is closing through the stop, then enter an order to sell your options.

But if you have a life and are not therefore tied to a trading screen (perhaps you were playing golf or were at work), then you would check your stocks when you get home at night. If the stock has closed through the stop, then exit your option position the next morning.

By the way, there are some who even use two-day closing stops before exiting a position (that is, the stock would have to close through the stop for two days before the position is closed).

Using closing stops has certain advantages and disadvantages over the “classic” straight stop in which you exit as soon as your stop price is touched. The advantage is that intraday wiggles in the market won’t take you out. At certain times, market makers or other participants will sometimes “fish” for stops – driving a stock down, say, looking to trigger sell stops. These fishermen then buy the stock that is for sale in the hope that there will be a quick rebound once the stop orders are run out of the market. Using a closing stop avoids those problems.

However, the closing stop may cost you more than the “classic” stop if the stock continues to move farther all day long. For example, suppose you are long IBM calls, and you have a mental closing stop at 100 on the stock, which opens the day at 100.20. Soon thereafter, IBM trades below 100 and continues to fall – eventually closing the day’s trading at 97. A straight “classic” stock would have exited as soon as the stock touched 100, in the morning. The person using the closing stop, though, suffers through another 3 points of downward IBM movement before exiting. In this scenario, the closing stop is more costly. For those who can’t be available for trading as the market is closing (4pm), but instead have to wait overnight to exit, there could be a substantial IBM price movement overnight, thus potentially adding to the costs of the closing stop.

We have weighed these factors over the years and feel comfortable using closing stops, especially on a stock that has momentum in our favor (that is, a stock in a strongly rising trend may suffer a brief intraday setback, but often recovers before the close).

Types of Trailing Stops

A trailing stop is any sort of moving average that “trails” the stock price. It could be something as simple as the 20- day simple moving average (never a bad choice), or a more complicated one, such as an exponential moving average. There are trailing stops that are volatility-based, which trail a parabolic rising stock more closely than a simple moving average (SMA). These include parabolic stops and chandelier stops. We use chandelier stops a great deal of the time, as we have found that it provides a better stop level – especially for a volatile stock. Chandelier Stop: there are a number of ways to calculate the Chandelier Stop, but we use the “traditional” one: the trailing Chandelier Sell Stop (if you are long the underlying) is equal to the highest high over the last 10 trading days minus 3 times the average true range1 over the last 10 trading days. The trailing Chandelier Buy Stop (if you are short the underlying) is equal to the lowest low over the last 10 trading days plus 3 times the average true range over the last 10 trading days.

The “volatility-based” part of this stop is that it uses average true range, which expands when stocks are volatile and shrinks when they are not. You may also want to Google “Chandelier Stop” and see where some technicians have altered the parameters to allow for altering the number of trading days and/or the constant (“3").

Partial Profit Strategies

Merely relying on the trailing stop is probably more than most humans can bear. It is devastating to see profits build up, but do nothing because the trailing stop hasn’t been triggered, and then see the stock reverse and stop the position out – causing a loss of (nearly) all of the profits.

So, most of us take partial profits so we can justify having booked “something” in case the stock then falls. Normally, this partial profit strategy would entail selling 1/4th to 1/3rd of the position. If we’re long, and if the stock goes higher, we’re happy because we still have a majority of our original position. But should we be?

The sale of part of the position cuts off all profits from that portion later on. Thus, if we’re right about being long the stock or its call options, and it does indeed trade much higher, we’ve left a bunch of profits on the table – much as those operating with targets do (at least on that fractional portion).

Even so, most traders prefer to take some partial profits rather than risk the entire profit. These partial profits are usually taken fairly early in the life of the position – on the first profitable move of any size.

It’s hard to estimate what the overall cost of this strategy is, because there are so many possible outcomes after a partial profit is taken. But we know for certain that, if the stock moves higher at all from the level at which partial profits were taken, the taking of partial profits harms the overall return on the position.

Changing The Strike – Rolling Up or Down

Another tactic that traders use in order to reduce exposure on a possible extended position is to roll the option from one striking price to another (and possibly to another month as well). This usually arises after a stock has made a rather large, and probably sudden move. Consider this situation:

Example: you are long 8 of the XYZ August 40

calls. The current relevant prices are:

XYZ Stock: 50

Aug 40 call: 10.50

Aug 50 call: 3.00

Chandelier Stop Price: 44.50

Apparently, this stock is advancing so quickly

that even the Chandelier Stop can’t keep pace.

There is currently a 5.50-point difference between

the current stock price and the trailing stop price.

That is a large amount, and makes most investors

nervous that they would be “forced” to hold for a

5.50-point drop if they are faithfully adhering to

the trailing stop price. By the way, note that the

price originally paid for the August 40 call is not

relevant to a follow-up decision, and therefore

isn’t a consideration. You should be making

follow-up decisions based on current market

information.

One way around this is to roll the options up to

a higher striking price:

Sell 8 Aug 40 call @ 10.50

Buy 8 Aug 50 call @ 3.00

For a credit of 7.50 per spread

By rolling up, one accomplishes several things:

1) he takes $750 per option in credit out of

the position and puts it in his pocket.

2) he reduces his risk. Now, the worst that he

can do is give back $300 – the price paid

for the Aug 50 call.

3) he still has upside profit potential if the

stock continues to rise, since he is long

the same number of calls as before (8) –

just at a higher strike now.This seems like such a winning strategy that traders are often too quick to use it. What is the downside? One once again is leaving money on the table. Analyze the roll itself:

Buy Aug 50 call

Sell Aug 40 callThat is a bear spread. In other words, you are overlaying a bearish trade on top of your long call position. If the stock continues higher you will have harmed your profit potential by the loss on this bear spread.

If you look at this trade as a mere bear spread, you are receiving 7.50 credit, and the maximum payout if the stock is above 50 at expiration would be 10 points – the difference in the striking prices. Therefore, if the stock continues higher, you have given away 2.50 per option.

Even so, many traders will execute this roll because they fear that they will be hamstrung by forcing to adhere to the trailing stop, which is currently so far below the stock price (5.50 points). Note that rolling down, when one is long puts is similar – in that case, you would be overlaying a bullish spread on top of your long put position.

Is there a better time than others to roll up? Generally, the best time is when you are not giving up too much profit potential with the roll. That can be determined by comparing the difference in the striking prices with the credit received from rolling up. In the above example, the distance in the strikes is 10 points, and the credit received is 7.50 – 75% of the striking price differential. That’s about the minimum percentage I would accept.

Clearly, the larger the credit in relation to the difference in the strikes, the less you are giving away by rolling up. If you can roll up for a 9.50 credit, for example, when the strikes are 10 points apart, you’d do that almost every time (unless expiration was nigh).

There are other strategies, but the above ones are the major ones. For example, you could buy an at-themoney put against a deeply in-the-money long call. That is exactly the same as rolling up, so it need not be discussed separately. Alternatively, you could sell an outof- the-money call against your currently long calls. That cuts off your upside profit potential, without greatly improving your lot if the stock should suddenly drop. So, that’s such a poor choice that we won’t discuss it, as it is never recommended by us.

The Cost of Taking Partial Profits

So what is the cost of these partial profit strategies? It’s impossible to quantify, of course, since the answer depends on what happens to the stock after the partial profit adjustment is made.

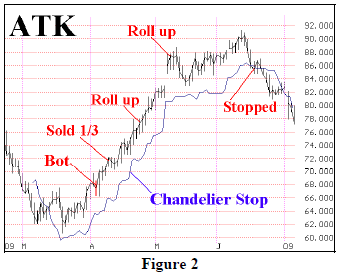

Let’s look at one specific, recent example – the call buy that we had in Alliant Tech (ATK). Here are the transactions we made:

Date Trade Stock Trailing

Price Stop

4/3/09 B 3 May 65c @ 5.70 68.16 65

4/9 S 1 May 65c @ 8.00 71.83 67

4/16 74.17 68

4/24 Roll up:

S 2 May 65c @ 11.10 76.72 n/a

B 2 May 75c @ 3.50

4/30 79.65 74

5/8 Roll up and out:

S 2 May 75c @ 11.50 86.49 n/a

B 2 June 85c @ 4.40

5/21 85.25 82

6/4 88.30 84

6/11 90.06 86

6/17 Stopped out:

S 2 June 85c @ 0.85 85.44 86

Total Profit: +22.00 pointsATK stock moved from 68.16 on April 3rd to 85.44 on June 17th, before being stopped out. We took a partial profit on 1/3rd of the position on April 9th, then rolled up twice more as options got 10 points in the money – and well above the trailing stops – on both April 24th and May 8th. Figure 2 recaps these data points, graphically.

The total profit, before commissions, was +22.00 points ($2,200). If we had never rolled – except at May expiration – the profit would have been on the order of 43 points, a 21-point difference – just about twice as much! Hence, taking partial profits and rolling up wasted about half the profitability of the position. The first roll up – selling two 10-point spreads for 7.60 credit – cost 4.80 points. The second roll up – selling two 10-point spreads for 7.10 credit – cost 5.80 points. Therefore, the big culprit was the initial partial profit, which, by subtraction, cost 10.40 points (4.80 + 5.80 + 10.40 = 21.00).

Clearly, if we knew that the underlying was going to continue to rise as dramatically and steadily, then we would never take any partial profit at all. But, in real life, that doesn’t happen very often. It’s more likely that a quick stock price gain will suddenly be offset by a retracement of some sort. In that case, the partial profit strategy makes more sense.

The only way to tell for sure, though, would be to take a number of actual trades and compare the results of the partial profit strategies as we applied them vs. a strategy of doing nothing other than minding the trailing stop. We will reserve that study for another article.

Summary

There are a number of ways that a trader can handle a profitable speculative position as it unfolds. We prefer the trailing stop approach, because that is the way that one can let his profits run. The trailing stop gives a firm guideline as to when to sell the position, so that the trader does not have to fall prey to his psychological frailties as profits build up. The further question, though, is whether partial profit strategies do more harm than good. That answer will have to wait for another day.

This article was originally published in The Option Strategist Newsletter Volume 18, No. 13 on July 10, 2009.

© 2023 The Option Strategist | McMillan Analysis Corporation