By Lawrence G. McMillan

This article was originally published in The Option Strategist Newsletter Volume 12, No. 7 on April 10, 2003.

A subscriber recently asked the question, “If the market is breaking down and options are expensive, would a call credit spread be the best low risk spreading strategy to use?” It’s a good question, and the answer gets into a dichotomy of sorts – in that a credit spread might not be the best strategy even when options are expensive.

It is sort of a “knee-jerk” assumption that a credit spread will do better than a debit spread if volatility collapses. In reality, that’s not true. If they both employ the same strikes, they will perform the same (otherwise, risk-free arbitrage would be available).

Furthermore, if one establishes a credit spread, he will most likely do it with out-of-the-money options (to correctly lower his risk of early assignment), but that often offers lower profit potential than the typical debit spread – which probably also utilizes out-of-the-money options.

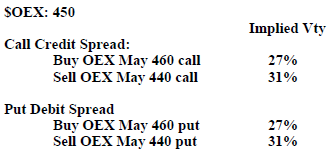

Let’s look at some specific examples. As a first assumption, let’s say we’re bearish and that implied volatility is high (as the reader’s question suggested). So we’d either want to sell a call credit spread or buy a put debit spread. In either case, the volatility skew would be in our favor if we’re using index options – since both spreads involve buying an option with a higher strike and selling one with a lower strike. Given the way that index options behave (see the volatility skew tables on page 6), this means that we’re buying an option with a lower implied volatility than the one we’re selling – in either type of spread – and that’s statistically attractive.

Since these two spreads utilize the same strikes, they will behave in a similar manner. If they didn’t, something called “Box arbitrage” (risk-free arbitrage) would beavailable.1 So, in this sense, the two spreads would be equal.

Also, it should be pointed out that the vega of the two spreads would be the same. “Vega” is the amount by which the option (or spread) price changes when volatility changes. In this case, since volatility is expensive, one would want a position with negative vega – something that would make some money if volatility declined. Since a put and a call at the same strike have the same vega, these two spreads have equal vegas – and hence they respond in the same manner when implied volatility changes. So, there is no advantage to either one in that regard. In fact, a call credit spread and a put debit spread, utilizing the same striking prices and expiration months, are equivalent positions, so there is no inherent advantage to either one – except perhaps for the fact that the credit spread is more likely to be a candidate for early assignment, if that situation should arise.

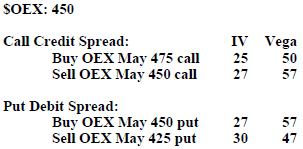

In actual trading, though, one would probably not establish either of the spreads shown above. Rather he would probably want to choose between one of these two:

In fact, one might even use further out-of-the-money calls for a credit spread, but let’s analyze these two somewhat symmetrical spreads – each one using an at-the-money option as its “main” leg and then using an out-of-themoney option to complete the spread.

You will notice that both spreads still have favorable implied volatilities with respect to the volatility skew – an option with a lower implied volatility is being bought and one with a higher implied volatility is being sold, in both spreads.

However, vega is now favored by the credit spread. The call spread has a vega of –7 (the long call’s vega, 50, minus the short call’s vega, 57). This means the call spread will profit by 0.07 points for each percentage point drop in implied volatility. The debit\ spread, on the other hand, has an unfavorable outlook with respect to a decline in volatility: the long put’s vega, 57, minus the short puts vega, 47, gives the put debit spread a vega of +10. This means it loses 0.10 points for each one percentage point decrease in implied volatility. Hence the credit spread is more favorably situated for a decline in implied volatility – something that is intuitive to most experienced option traders, but might not be obvious to all.

However, the discussion doesn’t end there. The profit potential of the debit spread is usually greater than that of a similar credit spread – at least given the way that most traders implement them. Typically one would establish a credit spread with both options out-of-themoney – different from the preceding example. When one establishes the credit spread that way, the profit potential is rather small since the initial credit received would be relatively small, with both options having started out-ofthe- money. On the other hand, the debit spread often has larger profit potential because the debit paid is usually less than half – often, far less than half – of the distance between the strikes in the spread.

One other point: depending on the strikes used, the probability of profit is probably higher for the credit spread, since both options are typically out of the money to begin with – and that is not usually the case for a debit spread.

Finally, the matter of early assignment once again favors the debit spread. The only time a debit spreader would face early assignment would be if the underlying has already moved in his favor by a great deal. In the put spread, if the underlying falls so far as to place the short put in a debit spread in jeopardy of early assignment, the spread will have widened out to its maximum profit potential. The credit spreader, however, will only encounter the possibility of early assignment if the underlying has moved against him. In a call credit spread, if the underlying rallies so far as to place the short call in jeopardy of early assignment, that means the spread has lost quite a bit and is in danger of losing more.

In general, I tend to favor debit spreads because I only use them when we have a directional signal working in our favor – and I want to make the larger profit available with the debit spread. If I want to capture” high volatility,” then a credit spread is acceptable (provided that the striking prices are not too far out-oft h e - m o n e y ) , although we often recommend naked options or ratio spreads (which also involve naked options) because they are a “purer” play on volatility.

This article was originally published in The Option Strategist Newsletter Volume 12, No. 7 on April 10, 2003.

© 2023 The Option Strategist | McMillan Analysis Corporation