By Lawrence G. McMillan

This article was originally published in The Option Strategist Newsletter Volume 13, No. 4 on February 26, 2004.

As we’ve mentioned before, the CBOE is about to offer us the ability to trade volatility. We expect this to be a very successful product – perhaps the most successful new listed derivative product since the introduction of index options over 20 years ago. We want you, our readers, to be prepared for this event. Hence, we will run a series of short articles prior to their introduction, to ensure that everyone knows the facts and understands the basic strategies.

Backgrond and Mechanics

The $VIX Index – created to measure implied volatility of $OEX options – was introduced in 1993. Last year, the CBOE changed the $VIX to be the measure of implied volatility of S&P 500 Index ($SPX) options. The “old” $VIX became $VXO and that index still measures the implied volatility of $OEX options.

Now, the CBOE has created a futures exchange (the “CFE”) and its sole initial product will be futures on the $VIX. To implement this contract, a new volatility index, called the Jumbo CBOE Volatility Index (symbol: VXB) will be disseminated. VXB will be equal to 10 times VIX. The futures will be futures on the Jumbo VIX and will be worth $100 per point of movement. So one futures contract will make or lose $1000 when $VIX moves by 1 full point (from 15.00 to 16.00, for example).

You will have to open a futures account in order to trade these futures – as you do with any other futures. Despite earlier projections to the contrary, you cannot trade them in your regular stock account.

The futures will trade with the base symbol VX, and will expire in Feb, May, Aug, and Nov, plus there will be a contract in each of the two nearest months not included in that February cycle. There will be four months available for trading at any one time. So, if today were June 1st, then there would be contracts expiring in June, July, August, and November. (Ed: if the contracts prove to be successful, there will probably be additional months added). The minimum tick in the volatility futures is 0.10 (which is the same as 0.01 for $VIX) and is worth $10.

The VX futures will have different expiration dates than CBOE-listed index options. The last trading day will be the Tuesday immediately before the 3rd Friday of the expiration month. The actual settlement price, though, will be determined on the Wednesday morning following that Tuesday. In a procedure somewhat similar to the “a.m. settlement” that exists for most cash-based index options, a “Special Opening Quotation” (symbol: SOQ) of VIX will be calculated from the opening price of the options used to calculate the index on the settlement date (the Wednesday morning in question). The opening price for any series in which there is no trade shall be the average of that option's bid price and ask price as determined at the opening of trading. The final settlement price will be rounded to the nearest 0.10. The futures will then settle for cash at a price equal to 10 times that “Special Opening Quotation.”

Futures must be margined. The margin requirements will be set by the Exchange, and they have not been made public yet. But generally, index futures have margin based on volatility – approximately equal to 20% or less of their value. The CBOE has stated that they will allow SPAN margin to be used – a volatility-based margin calculation, which is generally favorable to customers.

Example: On April 1st, suppose that $VIX is trading at 16.48 and that the May VX futures are trading at 174.3 (they will have some premium in them, most likely). You buy one May VX futures contract at a price of 174.30.

Since the futures contract is worth $100 per point, and you paid 174.30 for this contract, you are therefore “controlling” $17,430 worth of $VIX initially. Let’s suppose the margin for this trade is $3000. That can be satisfied with equity from your account.

Suppose that shortly after your purchase, the stock market rallies and $VIX drops quickly to 16.05 – a drop of 0.43 points. Your futures will drop accordingly, but not by necessarily that exact comparable amount, which would be 4.30. If panic selling sets in, they could lose some of their premium. Let’s say that the futures you own drop to 169.00 and the market closes. You now have a loss of 5.3 points on your futures. A one point move is worth $100, so you have a $530 loss (unrealized) at this time. Your account is debited that amount, and the margin calculations are redone to see if you are still in compliance. If you fall below maintenance margin requirements, your broker will ask for more margin (and will sell you out if you fail to comply – just as would happen with stock bought on margin).

Let’s say you hold on and $VIX rallies over the next few weeks, and expiration day has arrived. You decide not to sell your futures in the open market, but rather to let them settle for cash on expiration day. Remember, each day, the daily profit or loss is credited or debited to or from your account. On the last day, suppose that the “Special option quotation” for $VIX is 21.40. Your futures would then settle at a price of 214. That’s a profit of 29.70 points from your initial purchase price of 174.30. You would have made $2,970 less commission on the trade. Since you held them all the way to settlement, the last day’s P&L is debited or credited and the futures disappear from your account. The sum of all the daily debits and credits will total $2,970, so that much cash would have accumulated in your account (assuming you didn’t use it for something else in the meantime) and the futures would no longer be in your account.

The Strategies

We will cover strategies in the next few newsletters. Some were described back in Volume 12, No. 17, but we will go over them again, since we have many new readers. The simplest strategy is speculation about the direction of volatility. But many professionals will use the futures to hedge volatility as well. Finally, plain vanilla stock owners should seriously consider using these futures as a hedge against a bear market. They are likely to be more useful than index puts are (although they are also likely to be similarly expensive).

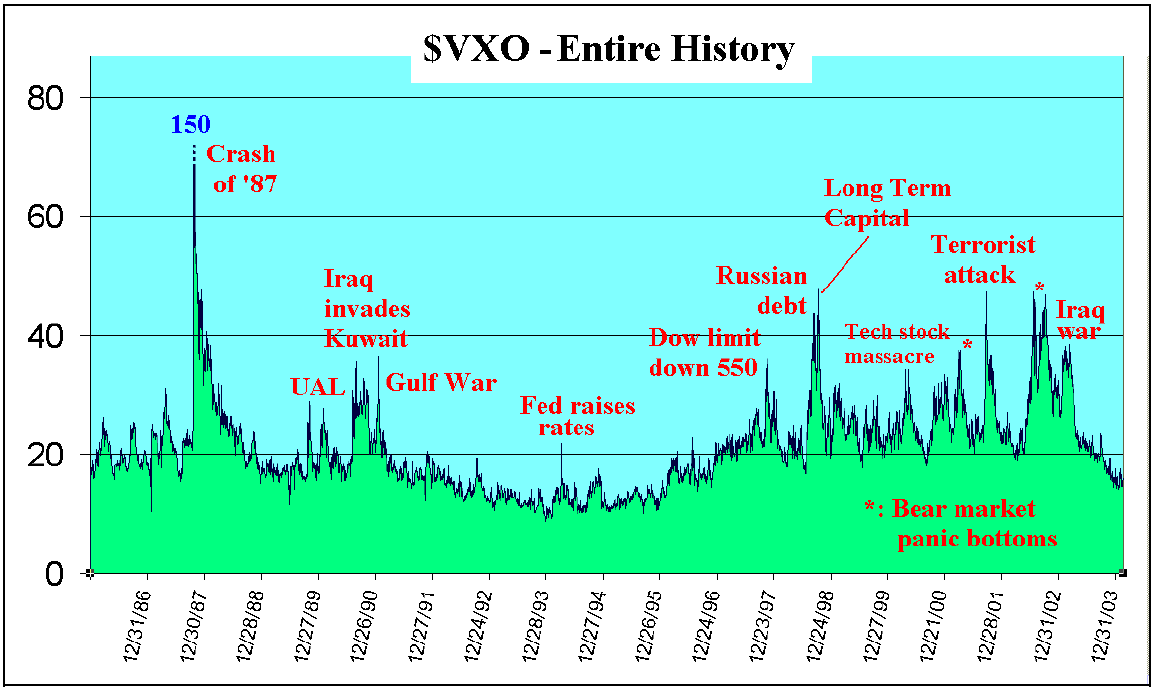

On the last page of this newsletter, there is a full page graph of the history of $VXO. $VIX has a similar history, but $VXO’s is longer, so that’s why we used it (when the CBOE introduced this index in 1993, they calculated the data back through 1/1/86).

Several things are apparent from this long-term chart. One is that $VXO trades at all sorts of different levels – from 10 to 60 and above. Thus, it is incorrect to say that a fixed level is a buy or sell signal. For example, some of the spike peaks occurred with $VXO in the low to mid-20's (Gulf War, or when the Fed raised rates in 1994). On the other hand, $VXO rarely ever traded below 20 from 1996 through 2002. So, a dynamic interpretation is necessary – as it is with most market indicators. One identifies spike peaks – wherever they might occur – as long as they accompany a swiftly declining $OEX Index.

The long history of $VXO shows several distinct periods and trading ranges. First, there was the 1986 - 1990 time period, when $VXO often traded above 20, and large spikes occurred at the 30 level or higher (not to mention the 150 level reached in the Crash of ‘87 – a level never approached, since). But then the market became docile from 1991through 1995, with $VXO trading down to its all-time lows below 10 and rarely getting above 20. However, that all began to change in 1996, when $VXO increased all year. Then, from 1997 through about the first half of 2003, $VXO was consistently volatile – probably averaging near 30. Suddenly, the bull market that sprang up in March, 2003, issued in a period of steeply declining volatility, took $VXO down to levels not seen in eight years. So, $VXO can change complexion, and if you’re planning on speculating in the $VXI futures, you’ll have to adapt to these changes in volatility – not just picking some fixed level of $VXO as “expensive” or “cheap” and stubbornly refusing to yield even as $VXO makes a new extreme high or low. In the next issue: hedging strategies for stock owners.

This article was originally published in The Option Strategist Newsletter Volume 13, No. 4 on February 26, 2004.

© 2023 The Option Strategist | McMillan Analysis Corporation