By Lawrence G. McMillan

This article was originally published in The Option Strategist Newsletter Volume 18, No. 22 on November 26, 2009.

No matter how you measure it, volatility is decreasing. There are several reasons for this – and we’ll discuss them in this article. In addition to traders’ perceptions about forthcoming actual volatility, there are some strategy-related influences, as well as seasonal influences, that are contributing to this most recent decline in volatility.

Let’s begin by noting that the CBOE’s Volatility Index ($VIX) is at or near its yearly lows and hasn’t been significantly lower since September, 2008, prior to the Lehman bankruptcy. The “old” $VIX – trading under the symbol $VXO since 2003 – has already closed at new yearly lows this week. $VIX is just slightly below 21, but $VXO is already approaching 19. While it is true that these volatility measures are based solely on the S&P 500 Index ($SPX) options that trade on the CBOE, they are and always have been a good measure of the overall mood and volatility of stocks in general.

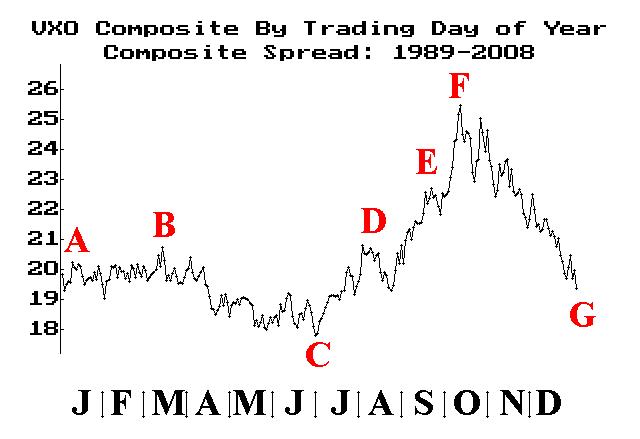

The seasonal chart of $VIX is shown on the right in Figure 1. Note that it is typical for volatility to reach its peak in October (point F) and then to decline into the holiday season, eventually bottoming out near Christmas, near the yearly lows (point G). Figure 1 uses $VXO data, rather than $VIX data, because the former data series extends back farther in time – allowing us to get 20 years of composite data into this chart.

While this year, 2009, has not conformed to the seasonality chart very well, the latter part of the year does seem to be falling into line. $VIX spiked up to 32 when the market had its last minor correction at the end of October. Since then, it has been falling steadily, and is now making new yearly closing lows (see $VIX chart, page 11).

It seems to be an annual rite that traders get caught in this “volatility vortex” and lose money because of it. That’s probably due to the fact that traders get used to the increasing volatility in September and October and then have trouble getting in line with the rather severe volatility decrease that takes place in November and December.

I get the feeling that this has once again been the case this year. Many option traders were buying puts heavily, expecting a market correction in September or October. When prices finally broke down in late October (a 70-point $SPX decline in about two weeks), they bought even more puts, paying up dearly for them. That drove $VIX to 32. But few of those same traders have been able to reverse course, as the stock market has rallied and volatility has collapsed.

This hedging activity is one of the influences that we referred to at the beginning of this article. We have been noting for months that these hedgers have been buying puts in anticipation of a (severe) market correction this fall. It did not happen, though. As a result, their hedges bought for August, September, October, and November expired worthless for the most part. Yes, they owned stock and that was profitable, but the hedging cost most likely left them underperforming in terms of their benchmarks and their peers.

During that period of hedging, $VIX was routinely trading well above the historical volatility of $SPX and there was inordinate volume in put options. The 20-day historical volatility of $SPX is now 21%, which is roughly the same as $VIX. Does this mean that the hedgers have shut down? Not necessarily, for that 20- day “blip” in actual volatility still includes the late October correction. For example, the 10-day actual volatility is back down to 14%, which would leave $VIX at a substantial premium once again – and could clear the way for even lower $VIX readings in the near term.

But even if the hedgers understand the near-term volatility implications, that doesn’t mean they’ve given up altogether. It is highly likely that they are buying puts out in January, February and March of 2010 since those months’ $VIX futures are trading with very large premiums (see the article on page 12).

So, the recent collapse in $VIX – which has been mirrored by nearly all stock and index options alike – is partly due to seasonality, partly due to the resumption of the market rally (which lowers actual volatility), and partly due to reduced demand from hedgers (who – if they are still hedging are buying longer-dated options1).

This decrease in volatility causes severe problems for option writers. They are suddenly faced with lowering their risk standards (for example, writing puts with a higher probability of reaching the downside breakeven price) or standing aside. Even rolls are terrible. Consider Johnson & Johnson (JNJ) as an example. This is a stock which we write against in many of our managed accounts. The stock recently reached the 62-63 area, so we looked to roll up Jan 60 calls that we have written against stock. There is no month at which the 65 strike can be rolled into for a credit – not even the Jan 2011 LEAPS calls! This is caused by the low volatility. JNJ has just jumped five points this month – and yet no one is willing to pay a “reasonable” price for a 65 call? That’s the way things are lining up right now. Massive numbers of owners of JNJ stock, who are fearful of a general market decline, are writing or have written JNJ calls and thus are keeping the price depressed.

Realistically, we probably can’t expect much of an increase in vol unless there is another stock market correction in the near term. That is always possible, of course, and is perhaps even more possible, given the large number of times that my TV has recently told me that traders are shutting down for the year to lock in profits, and thus don’t want any more risk this year. If that’s a consensus, then it could be “faded.”

Strategy

In any case, from a strategic viewpoint, we need to decide if we can take advantage of this information. Can we make a trade based on further declines in volatility this year, and/or can we set up trades that might profit when volatility inevitably rises again?

As one example, let’s take a look at Crude Oil. The CBOE publishes a “$VIX” for Oil, Gold, and the Euro (foreign currency), based on option markets in the active ETF options for each product. The $VIX formula is flexible. As long as there are active option markets in the two near-term strips of options (i.e., from the lower strikes continuously to the higher strikes), a $VIX can be calculated. These three volatility measures can be quoted on any quote machine, but there are no futures or options on any of them:

CBOE Crude Oil Volatility Index ($OVX) – based on USO option markets

CBOE Gold Volatility Index ($GVZ) – based on GLD option markets

CBOE EuroCurrency Volatility Index ($EVZ) – based on FXE option market

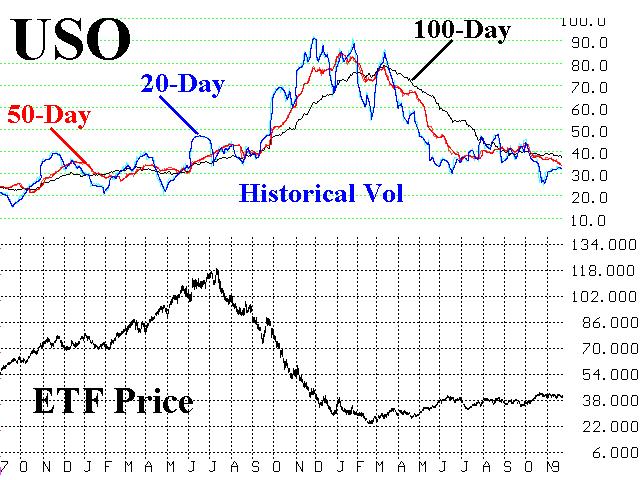

The chart of the Crude Oil $VIX is shown in Figure 3, as is a chart of USO (the United States Oil Fund) along with the historic volatility of USO, as Figure 2. Note: a continuous chart of Crude Oil futures and its historic volatility is virtually the same as that of USO. Similarly the “composite implied volatility” that we calculate daily for USO tracks well with $OVX.

$OVX (implied volatility) peaked last December, well before USO made its lows in February. That’s a bit unusual, but 20-day historical volatility also peaked in December, so perhaps that’s what option traders were using as a sort of “baseline” (similar to what stock option traders were doing at that time of turmoil in the financial markets).

Both historical and implied volatilities have, of course, fallen since oil made its lows. But implieds had remained well above historicals – just as was the case with $VIX and $SPX – until in the last month, the 20-day historical volatility of USO has increased from about 25 to 32, while $OVX has continued to fall – from 42 to 35. But now that they are in line at lower levels, is a straddle purchase or some other “long volatility” strategy viable? Not by reasonable statistical analysis. A fivemonth straddle on USO costs about 8 points. USO has been unable to move 8 points on either side of 38, since first reaching that level in June. In the last month, Crude Oil has been locked in such a tight range that a breakout is inevitable, but the options are already priced for a substantial move.

So, despite the lowest implied volatilities since $OVX was conceived, there is no “edge” in a long volatility position. This is a microcosm of what’s taking place everywhere: implied volatility is low and dropping even farther. But statistical (historic) volatilities are low, too, so that there really is no edge in many long straddles.

The problem here, in my opinion, is that nearly all the vols are decreasing. We would prefer to buy volatility when it is increasing, just as one would prefer to buy a stock in an uptrend.

We create straddle lists of this type on The Strategy Zone. For months, these lists were basically empty, but now they are beginning to be populated with viable candidates. Returning once again to the JNJ example, the 20- and 50-day historical volatilities of JNJ have been increasing since early October. That alone doesn’t mean that JNJ straddles are a buy (nor that JNJ is due for a decline), but it is the sort of data that is part of a good straddle buy.

At the current time, there is an increasing number of such stocks. Over 900 stocks have cheap options in our Extreme Volatility list on the Strategy Zone, and nearly 100 different stocks theoretically qualify as straddle buys under our requirements, as revised after the last big volatility “drain” (in 2005-2006):

1) 10-, 20-, and 30-day historical vols must have increased over the last 30 days.

2) implied vol must be lower than all three historicals

3) when implied vol crosses above at least one of the three historicals, then a straddle buy can be considered.

Once a straddle appears as a potential buy, then we look at the chart to visually see if the required moves are possible. We also consider the probabilities of success, based on our Probability Calculator which uses a Monte Carlo approach to calculate the probabilities. Finally, we consider liquidity – are the option markets relatively tight, and is there at least a modicum of open interest?

This article was originally published in The Option Strategist Newsletter Volume 18, No. 22 on November 26, 2009.

© 2023 The Option Strategist | McMillan Analysis Corporation