By Lawrence G. McMillan

This article was originally published in The Option Strategist Newsletter Volume 21, No. 10 on June 1, 2012.

These days, there are more and more volatility indices and futures than ever. One can observe the same sorts of things about them that we do with $VIX futures – in particular, the futures premium and the term structure. We thought it would be an interesting exercise to see how these other markets’ futures constructs compare to that of $VIX. The $VIX construct, for a long time (see chart, page 12) has been that of large futures premiums and a steep upward slope to the term structure. Historically, that sort of construct has been associated with bullish markets, although it has persisted throughout the current market decline as well. How do these other markets line up in comparison to the $VIX futures construct?

Background

Volatility Futures

In these articles, we like to lay out the definitions, so that readers who are not familiar with the terms can understand the article without having to refer to back issues.

The premium on a $VIX futures contract is merely the futures price minus the value of $VIX. Premium is a positive number if the futures are trading at a higher price than $VIX, but premium can also be a negative number – particularly in bearish markets.

The term structure of any group of futures describes their relationship to each other. The term structure is said to have a positive slope if each successive futures contract is trading at a higher price than its immediate predecessor. The following prices are an example of a positive slope:

| $VIX June Futures: | 23.00 |

| $VIX July Futures: | 24.80 |

| $VIX Aug Futures: | 25.60 |

| $VIX Sept Futures: | 26.40 |

| $VIX Oct Futures: | 27.25 |

The term structure has a negative slope if each successive contract is trading at a lower price than its immediate predecessor, as in this example:

| $VIX June Futures: | 33.00 |

| $VIX July Futures: | 31.60 |

| $VIX Aug Futures: | 30.25 |

| $VIX Sept Futures: | 29.60 |

| $VIX Oct Futures: | 29.00 |

These term structures naturally arise in a trending market. In a bullish stock market trend, the positive slope occurs; in a bearish trend, the negative slope persists. Thus it is erroneous to say that “traders” are predicting that volatility will move to some specific level a few months out in time.

Typically the slope is steepest in the near-term futures, and then it flattens out where the longer-term futures are concerned. The above examples only show five futures months, but in $VIX futures, there are eight months traded.

Volatility Options

In order to have listed volatility options, it is necessary that 1) there be an underlying volatility index (such as $VIX), and 2) that there be futures on that index. The index itself cannot be traded directly, but the futures can, of course. The option contracts are based on the futures prices. In effect, until expiration is reached, the futures are the underlying contracts for the options. Hence June $VIX options have a different virtual underlying security (the $VIX June futures) than do July $VIX options (whose virtual underlying is the $VIX July futures).

Volatility ETN’s and ETF’s

Various ETF issuers (Barclays, Direxion, Guggenheim) have introduced ETN’s and ETF’s, based on volatility. These products were first listed in early 2009 and are becoming more and more popular with each passing day. Most of these are ETN’s, because they don’t fit into the classic definition of an ETF (where underlying securities are deposited in escrow and can be used to give the ETF a definitive value at any time). ETN’s, on the other hand, are a credit risk of the issuer (Barclays, etc.), so if the underwriter should go out of business, the ETN itself may become a creditor of the underwriter’s bankruptcy. Hence an ETN could lose much of its value in such a negatively extreme situation. See the related article on page 7.

Listed Volatility Markets

We all know that $VIX is really the “$SPX VIX.” In other words, the $VIX calculation is based on $SPX options. There are quite a few other volatility indices, but most of them do not have listed derivatives. We have mentioned most that do, in various issues of this newsletter, as they have been listed. These included: Emerging Markets $VIX Brazil $VIX Gold $VIX Crude Oil $VIX

New $VIX Product

On May 23rd, the CBOE began trading futures on the CBOE’s NASDAQ-100 Volatility Index ($VXN). The $VXN “VIX” is calculated based on $NDX options. The $VXN index has been in existence for a long time (over 10 years), but this is the first time that traders can actually trade NASDAQ volatility.

Most of the contract terms are the same as $VIX futures: futures on $VXN are worth $1,000 per point of movement; the expiration day is always a Wednesday – 30 days prior to the next expiration of $NDX options; the final settlement value is determined by an “a.m.” settlement process on expiration day; and the last trading day is the day before. The base symbol for these $VXN futures is VN. So far, trading activity has been minimal, and the open interest for the four current trading months of VN futures is a mere 15 contracts, total.

Foreign Volatility Markets

We have not previously discussed foreign volatility markets, but three other countries have listed volatility futures – in a manner similar to $VIX. These are VSTOXX (European volatility), Hong Kong, and Russia. VSTOXX futures and options trade on the Eurex Exchange. Quotes are at www.eurexchange.com. Hong Kong volatility futures can be quoted at http://www.hkex.com.hk/eng/ddp/Market_Summary.asp ?MarketId=1 (click on Volatility Index Futures in list) Russian volatility futures are found at: www.rts.ru/en/forts/contracts.html (click forward to end of list – symbols start with VX).

Liquidity can be sporadic. In Hong Kong, open interest is 26 contracts for the three futures months listed. In Russia, it’s better: 174 open interest in two futures contracts. In VSTOXX, though, there is liquidity: open interest of over 140,000 contracts in eight contract months.

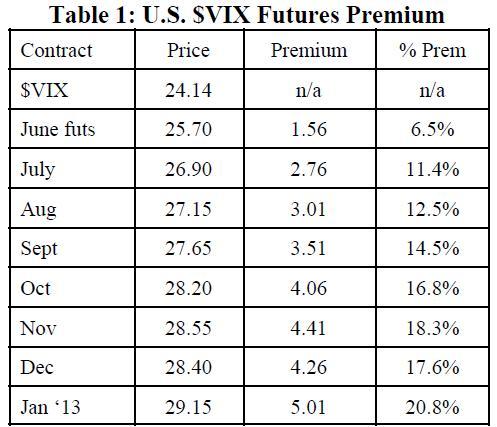

For the purposes of this discussion, we are only interested in the price quotes. The following table shows the premiums on (U.S.) $VIX futures. The “Premium” column is the futures price minus the $VIX price. The “% Premium” column is the premium divided by $VIX.

Table 1 shows the upward-sloping term structure of the (U.S.) $VIX futures. It is not nearly as steep as it has recently been, but it is clearly sloping upwards. Let’s compare that with the other markets.

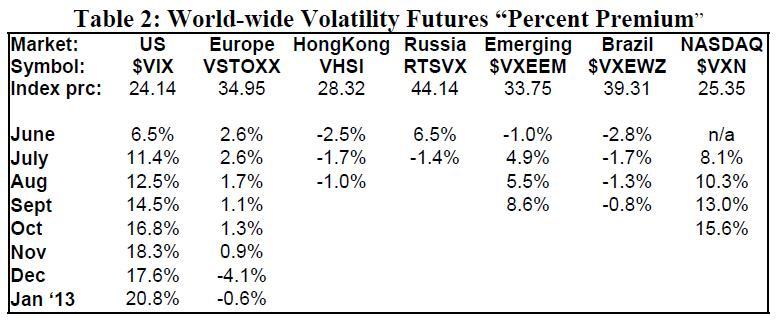

Table 2 shows the “percent premium” on the various other futures markets mentioned earlier in this article. Note that the first numerical column in Table 2 is the same as the “% Prem” column in Table 1.

Table 2 then proceeds to show the futures premium levels for all of the other markets. For example, consider the VSTOXX (European) data. The VSTOXX volatility index closed at 34.95 most recently (3rd row, 2nd column). Its June futures, however, settled with only a 2.6% premium. From there, looking farther out on the futures spectrum, the premiums actually shrink. In fact, the term structure is inverted for VSTOXX. The longestterm, January, futures are trading at a discount to VSTOXX itself (–0.6%). This is certainly a stark contrast to the $VIX futures.

In Hong Kong, a similar situation exists: the futures are trading at slight discounts to the Hong Kong volatility index, and the term structure is slightly inverted. Russia, with only two futures, confirms the same pattern: the futures premium is relatively small, and the term structure is inverted. Brazil has a slight upward slope, but futures that trade at a discount.

You cannot say that these are foreign markets, and they aren’t reliable. Brazil volatility products trade here in the U.S. – recently listed by on the CBOE Futures Exchange (CFE). European futures (VSTOXX) are very active and are traded by sophisticated hedge funds and other “smart” players.

Still referring to Table 2, the remaining two – Emerging Markets and NASDAQ – aren’t the same as the ones mentioned in the foregoing paragraph. Emerging markets ($VXEEM) has a positive-sloping term structure, but the premium levels are quite a bit lower than that of $VIX. The only one of the other markets that is similar to $VIX at all is the newly-listed $VXN. Frankly, it hasn’t been trading long enough (one week since inception) or in enough size to say that the futures are correctly priced. It may be the case that market makers are pricing the $VXN term structure similar to $VIX, for lack of a better pricing “model.”

What is causing this discrepancy?

So, the net effect of all of this is that the $VIX futures construct is the only one in the world that has such a huge premium on its futures and such a wildly upward-sloping term structure. Why? Why would Americans be so willing to pay up for protection in $VIX derivatives but not in other markets around the world?

It certainly seems to me that there is probably more risk in Europe and Russia et al than there is in the U.S. That’s not to say there isn’t risk here in the U.S., but the other risk derivatives markets should show similar symptoms.

One argument might be that these other venues have already seen a large increase in their volatility index, and that is what has caused the term structure to invert. That doesn’t really hold water, though. For example, the VSTOXX volatility index has risen from about 24 to 35 this year – a nice increase, but hardly one of such magnitude that it would account for the completely different patterns of its term structure vis-a-vis $VIX. The rises in the Hong Kong, $VXEEM, Russian, and $VXEWZ are all similar to VSTOXX.

If that were the real reason behind the inversion in the term structure, it would imply that a small additional rise in $VIX would result in the same inversion. That is not going to happen. It will probably take a relatively large rise in $VIX from here in order to invert the term structure.

So what could it be? What does $VIX have that nothing else has? Well, for one thing, it is tied to $SPX. Clearly the $SPX options in the later months are trading with the same term structure as the $VIX futures, else there would be arbitrage opportunities for sophisticated traders. But that’s not really an answer. It’s more of another way of asking the same question because saying that the $VIX futures term structure is the way it is because the $SPX option term structure is the same way, still doesn’t answer “Why?”

Could it be that Americans, and all other investors of the world who invest in the U.S., are so convinced that they need volatility ($VIX) or price ($SPX) protection that they almost don’t care what they pay for it? I think that’s getting towards the answer. But, still, why pay so much for it? What if they aren’t exactly aware that they are paying so much for protection? What if the products they are buying are masking the actual term structure?

The products that exist on $VIX and do not exist on any of the other foreign volatility markets discussed in this article are the volatility ETN’s and ETF’s that use the $VIX futures as their underlying. All of these eventually come down to a futures position. From the simple ones, such as VXX (long the two front month $VIX futures) to the more complex ones, such as XVIX (long a “double” package of $VIX mid-term futures and short a “single” package of the front month futures), these are all trading futures. The more the interest in the ETN, the more $VIX futures trading volume is generated.

ETN Mechanics

We have quite a few new subscribers this month, so I want to spend just one more brief moment reviewing how these ETN’s and ETF’s work. Longer-term subscribers can skip this section if they have a working knowledge of the volatility ETN’s.

Let’s use VXX (the Barclay’s short term volatility ETN) as an example. When a buyer buys “new” shares of VXX, Barclay’s “creates” those shares by buying the two near-term $VIX futures months in the appropriate ratio. For example, at the current time, VXX is long the June and July $VIX futures. As each day passes, the quantity of June futures diminishes and that of July futures increases. Hence, each day at the close of the trading, the Barclay’s manager has to sell June futures and buy July futures. This has the effect of pushing the near-term futures down and pushing the second-month futures up, all other things being equal.

This sort of daily rebalancing is being done all across the futures spectrum. VXZ – the Barclay’s intermediate-term volatility ETN – does the same thing with the fourth through seventh month $VIX futures. Other ETN’s and ETF’s behave in a similar manner, and the cumulative effect can be substantial. Over 63 million shares of VXX traded today, as well as 23 million shares of TVIX (double-speed VXX) and 21 million shares of XIV (inverse VXX). You can correctly say that VXX and XIV net each other out, but that still leaves 42 million “net” long VXX that has to be rolled.

The effect on the term structure

The purchase of new shares certainly contributes to, and might largely account for, the overall large premium in $VIX futures. Every time some new buyer comes into the ETN, a “new” set of shares is created by buying the appropriate $VIX futures contracts. That elevates futures premium.

But that alone wouldn’t account for the steep upward slope in the term structure. What would account for the term structure, though, is the fact that these ETN’s and ETF’s need to be re-balanced every night, at the close of trading. This constant upward pressure on the term structure certainly abets the steepness that we see.

This is not a new argument from us. We have said for some time that these ETN’s are affecting the term structure in ways that have not been seen before. What the ETN buyer does not see are the details of buying and rolling the $VIX futures. He doesn’t care, particularly, as long as the VXX ETN, say, behaves as he expects. That may be the rub, though. Recently, VXX rose from 16 to nearly 23, and is now at 20.5 (+28%). $VIX rose from 16 to 25 and is above 24 (+50%). That’s a big nonperformance. June $VIX futures rose from 20 to 28, and now are at 25.70 (+29%) – similar to VXX.

Much has been made in the media in the past of how the $VIX futures don’t perform as well as $VIX itself when the market collapses. Well, neither will these ETN’s. But they will provide some protection, and maybe that’s all their owners want.

For the rest of us, it creates opportunities to sell the overpriced futures and hedge that sale somehow. However, in the past, such hedges would profit as soon as demand for volatility slackened. In these times, however, with the continued demand for the volatility ETN’s, the hedge doesn’t really profit until expiration approaches or the stock market makes a big move. This can be a bit frustrating, as one is forced to hold such hedges for a longer time than required in the past.

This article was originally published in The Option Strategist Newsletter Volume 21, No. 10 on June 1, 2013.

© 2023 The Option Strategist | McMillan Analysis Corporation