By Lawrence G. McMillan

This article was originally published in The Option Strategist Newsletter Volume 6, No. 6 on March 27, 1997.

I was tempted not to label this article as a "basics" article, because the concept we're going to discuss is one that is probably not all that familiar to most option traders. It concerns the rate of decay of in- or at-the-money options versus that of out-of-the-money options. It's a concept that I realized I understood subconsciously, but not one that I had thought about specifically until I recently read Len Yates' article in The Option Vue Informer. Len is the owner and founder of Option Vue, creator of the software package of the same name and is one of the best option "thinkers" in the business (we are going to have a review of Option Vue when their new version is released).

Essentially, the concept is a simple one to describe: out-of-the-money options decay at a different rate than do at-the-money or in-the-money options. Specifically, out-of-the-moneys decay faster initially, and then more slowly as expiration approaches. Many traders are familiar with the rate of decay of an at-the-money option: it generally holds its value pretty well until expiration starts to get near, and then it decays rather rapidly as the expiration date arrives. Out-of-the-money options, on the other hand, behave in a much different manner: they will lose a good deal of their value in the first half of their life. Then — since there is less value left as expiration approaches — the decay, in terms of actual dollars (or points of value), is slower.

I say that I understood this concept subconsciously, because I always knew that — if you are selling naked options — you are far better off selling an out-of-the-money combo (both an out-of-the-money put and an out-of-the-money call) than you are selling a straddle (where the put and the call have the same strike). Conversely, when I buy options from a neutral viewpoint — volatility trading, for example — I rarely, if ever, buy the out-of-the-money combo. Rather, I prefer to buy a straddle whose strike price is near the price of the underlying instrument. As a subscriber, I'm sure you've noticed that whenever we sell naked options to take advantage of inflated volatility, we sell out-of-the-money combos. However, when we take advantage of low volatility, we buy straddles — not out-of-the-money options.

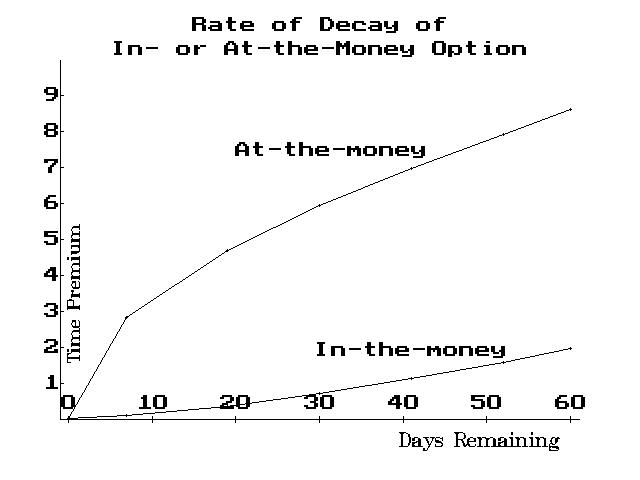

The above graphs show these effects of time decay. On the graph on top there are two curves. The higher curve shows the rate of decay of an at-the-money option. You can see that it begins to decay rather slowly as the remaining life in the option drops from 60 days to 30 days. However, in the last 30 days, the decay accelerates to the point where it looks like it is plunging downward during the last week of life of the option. The lower curve on that same graph (above, left) is that of the time value premium of an in-the-money option. It is a rather flat decay — almost linear.

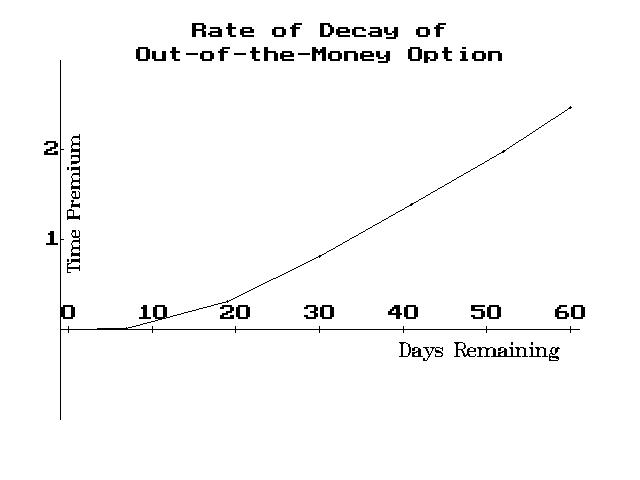

On the second graph is the contrast of the decay of the out-of the- money option. Its curve has a definitely different shape from the curve on the left. The out-of-the-money option decays rather quickly in the first half of its life, and then flattens out and decays more uniformly during the weeks leading up to and including expiration day.

This information has uses beyond merely deciding which type of option to utilize for neutral trading strategies. That is, what to buy when you want to go long, versus which type you want to sell naked. (For a direct option purchase — i.e., one in which you are merely using the option as leverage for trading the underlying instrument — we still generally prefer to buy the short-term, in-the-money option because it has a high delta. That is, it correlates well with the underlying price movement, and it has a minimal amount of time value premium).

Another conclusion that can be drawn from the above charts is that, if one sells out-of-the-money options with a slightly longer-term horizon, he might plan on covering them before expiration — perhaps just past the half-way point or so. He would do this, because a large majority of the time value decay would already have taken place, and therefore, the remaining opportunity would not be as great.

For example, suppose XYZ is trading at 100, and you sell the out-of-the-money combo, utilizing the calls with strike 120 and the puts with strike 80. The following table shows how much (unrealized) profit you would have from the naked sell combo if the stock was still at 100 one month, two months, etc.

Original Sale: Time Remaining In Options

| % Decay after... | 4-month | 3-month | 2-month | 1-month |

| 15 Days | 14% | 20% | 34% | 78% |

| 1 Month | 26% | 41% | 67% | 100% |

| 2 Month | 57% | 81% | 100% | --- |

| 3 Month | 86% | 100% | --- | --- |

| 4 Month | 100% | --- | --- | --- |

In general, you get nearly two-thirds of your time decay in just about the half the time to expiration. However, the table doesn't convince me that it's better to sell longer-term options. After all, if you sell the one-month combo, you get 78% of your time decay in just 15 days if the underlying is unchanged. That seems pretty good to me. Moreover, there's a much better chance that the underlying will still be hanging around its original price over a 15-day period than there is over a 3- or 4- month period. Of course, if you're talking about points of profit, the longer-term sales produce more dollars of profit, even if one were to assume that he could repeatedly sell the one month combos.

This article was originally published in The Option Strategist Newsletter Volume 6, No. 6 on March 27, 1997.

© 2023 The Option Strategist | McMillan Analysis Corporation